Project by Associate professors, Dr Elatiana Razafi & Dr Fabrice Wacalie with the University of New Caledonia

Blog with Dr Sylvia Frain, The Everyday Peace Initiative

The Pacific is diverse with over 1000 Austronesian languages, 750 Papuan languages and 9 variations of pidgin. From a sociolinguistic point of view, ‘pidgins’, ‘dialects’ and ‘creoles’, are all equally considered ‘languages’ as long as a social group recognises them as both a means of communication and identification.

While language diversity across Oceania is the norm and should be celebrated, UNESCO has identified hundreds of endangered languages across this region.

Negative representations of multilingualism are partly the cause of this. Research, however, has proven that speaking many languages has cognitive, perceptive, memory, and well-being benefits that help speakers build feelings of belongingness and self-confidence.

On a wider scale, the acceptance of linguistic diversity is also a key factor for peaceful and open-minded environments that welcome social diversity.

How many languages do you speak? How about your family members and elders?

Language is well-known as a communication tool but we also shape our social relationships and ways of thinking through languages. The feeling of belongingness is indeed linked to language use.

For instance, we spontaneously try to guess where someone comes from based on the way they speak. Likewise, linguistic features can also be used to correct, tease, discriminate or exclude someone.

Social rejection is caused by our subjective perceptions of a given language and how it should be spoken.

Discrimination based on language can become commonplace and invisible.

Elatiana Razafi and Fabrice Wacalie, researchers from the University of New Caledonia, refer to this as ‘linguistic micro-aggression’. Dr Chester Pierce, an African-American psychiatrist, medical doctor and scholar coined the term ‘micro-aggression’ in the 1970s. The word refers to ‘subtle racial putdowns that degrade physical health of a life time’ describes Elsa Ely. Drawing from this, the concept of “linguistic micro-aggressions” encompasses commonplace slights, corrective insults, normative comments that are specifically aimed at one’s language or linguistic characteristics as such their accent, pronunciation, vocabulary, or spelling.

It isn’t necessarily meant to harm but all the same, it reproduces dominant representations. This operates more frequently unconsciously. Nevertheless, and regardless of the speaker’s intentions, the effects can be damaging, especially when experienced by social minorities.

It can disrupt language maintenance within a family and this is particularly disturbing within communities who share endangered languages. New Caledonia is no exception to this.

Has anyone asked you, ‘where does your accent come from’? Have they commented on your pronunciation?

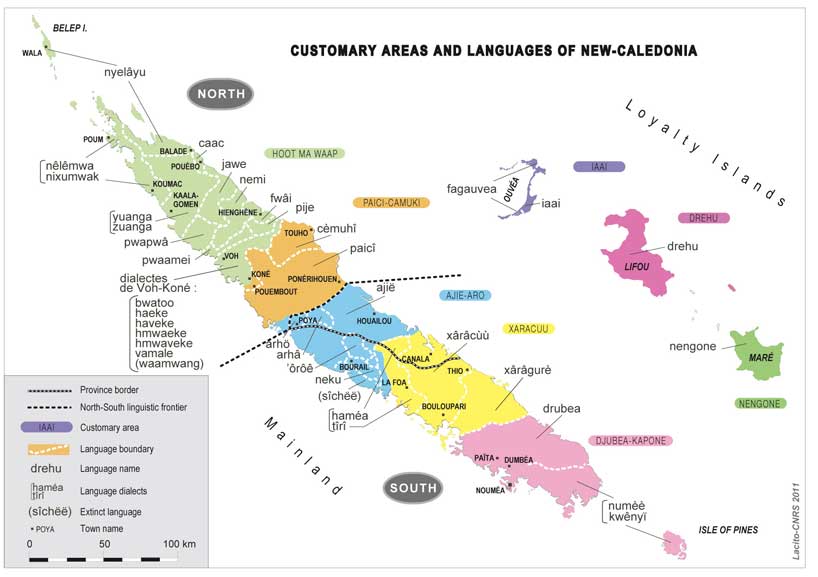

The archipelago of New Caledonia roughly consists of 40 ‘Indigenous’ Melanesian languages spoken, including a French Creole and alongside dozens of Polynesian and Asian languages.

Though proven beneficial, linguistic diversity or the ability to speak multiple languages can sometimes be subdued to a hegemonic monolingual policy. This leads to unequal access to social resources.

In New Caledonia, French is exclusively the single ‘official’ language as is the case throughout France’s territories. French dominates public services, such as education, media, administration. Consequently, linguistic diversity is often seen as trivial or even as a threat to national unity.

This part of New Caledonia’s historical colonial structures continues today through a monolingual ideology. It opposes Kanak and Oceanian languages versus French. Another less frequently addressed issue surrounds the variety of linguistic norms within Kanak languages themselves. Today, young students are working to challenge this artistically.

The AK-100 project: from linguistic micro-aggressions to artistic empowerment

The AK-100 street art project (reads ‘AK-cent’ in French in reference to the word ‘accent’ but also to the hundreds of languages and accents in New Caledonia) seeks to raise awareness of the destructive cultural impacts of ‘linguistic micro-aggressions’. As a form of symbolic violence, linguistic micro-aggressions engender feelings of exclusion, illegitimacy and, as narrated by young Caledonians, it leads to the abandon of Kanak languages when they are daily and durably marginalized. This means that there is a direct link between everyday communication patterns and sustaining larger scale linguistic diversity. A young student shares a family story, witnessing that the accumulation of linguistic micro-aggressions resulted in such discomfort that her father refrained himself from teaching her his native Kanak language.

Do you know similar stories of parents not passing on their language to their children?

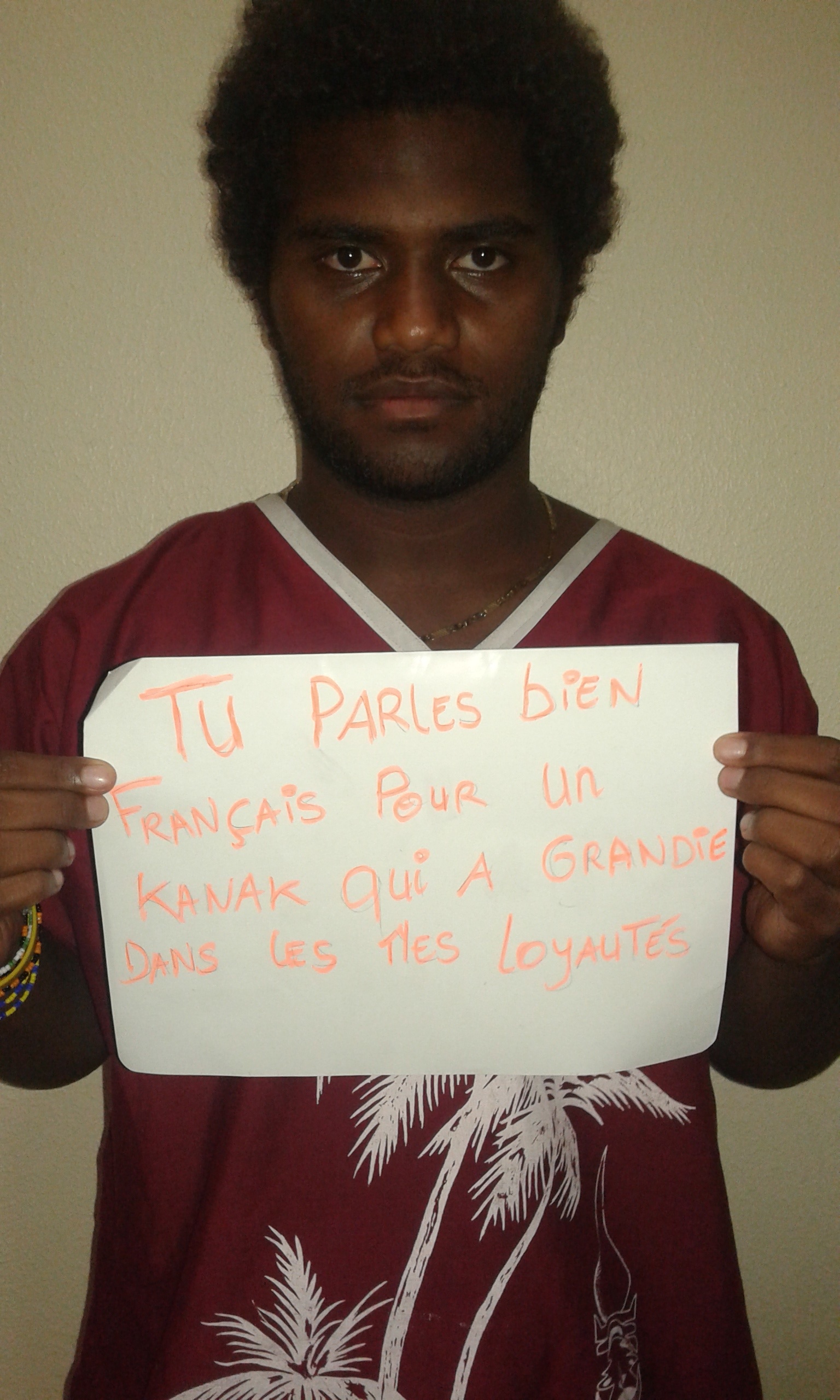

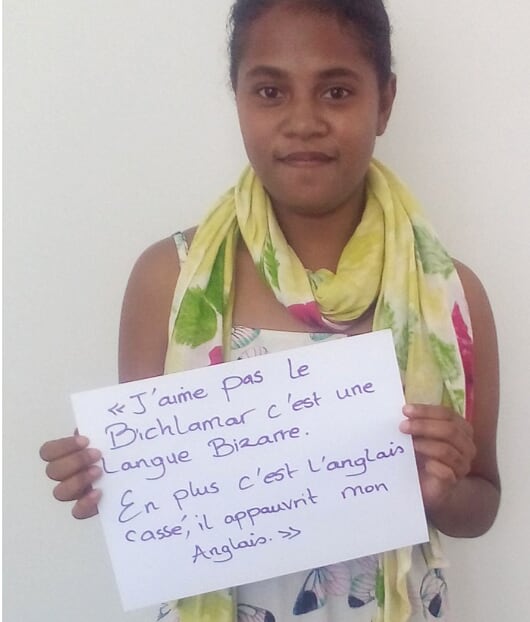

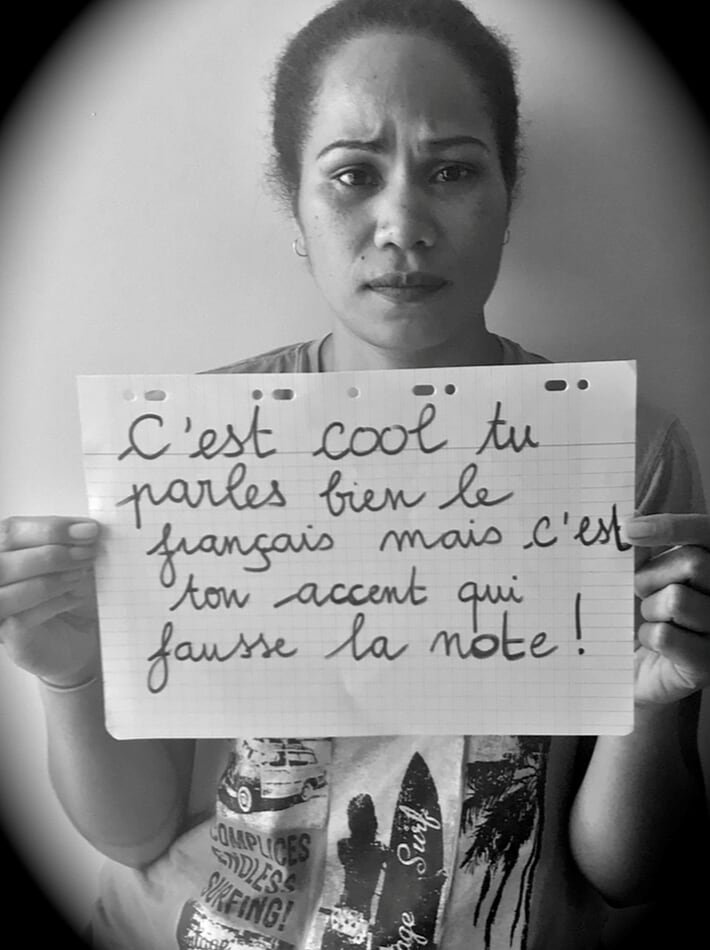

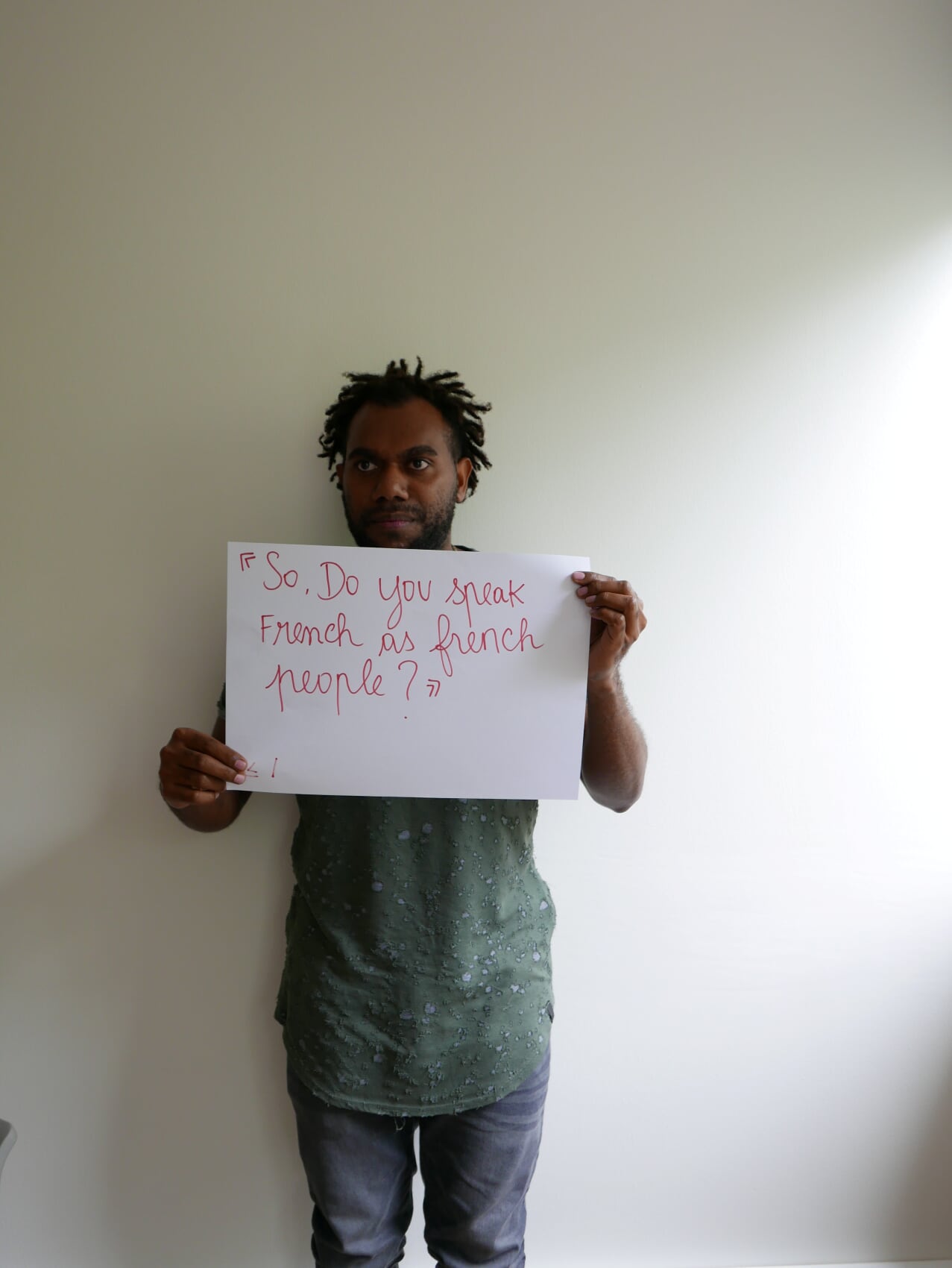

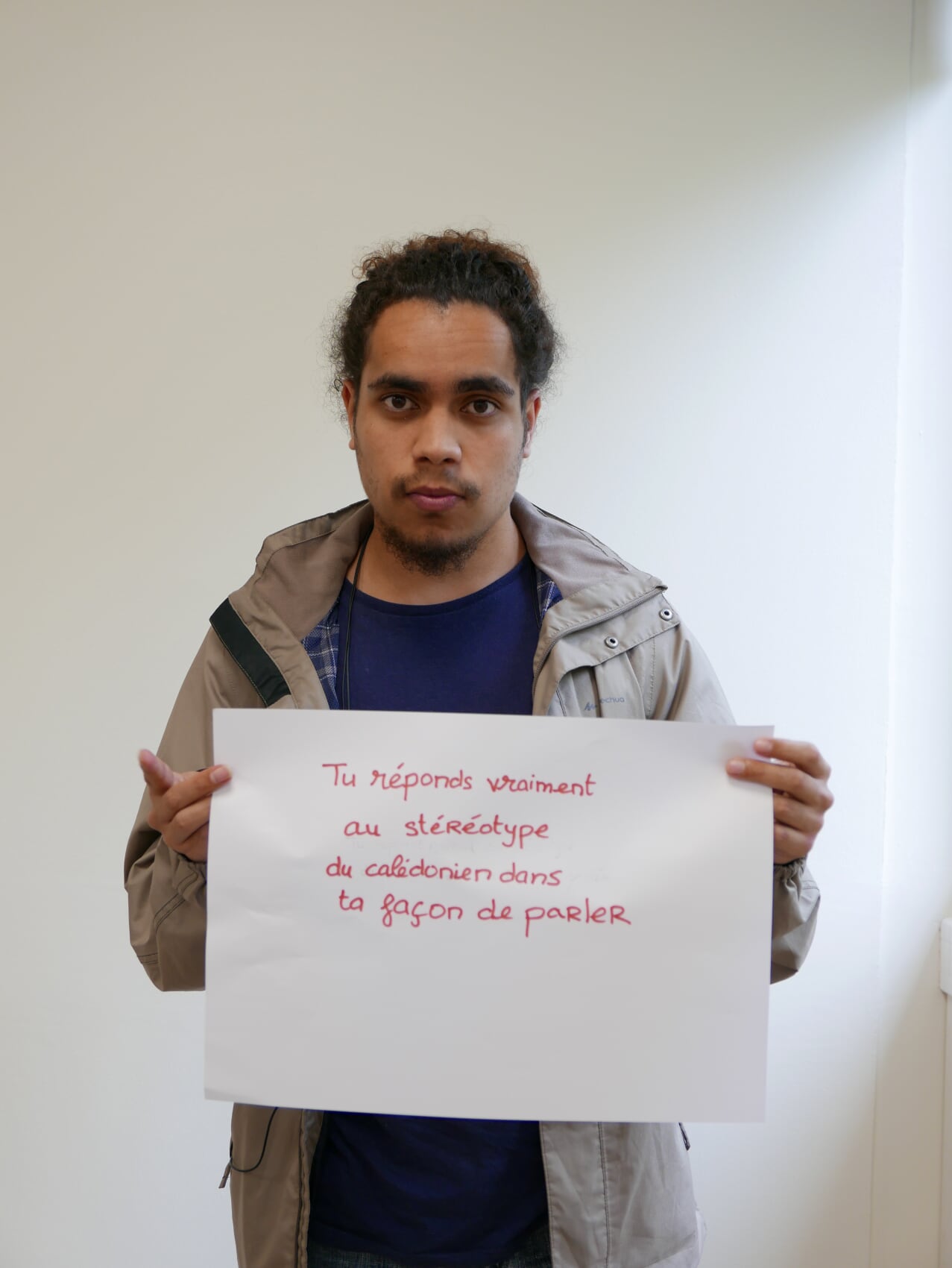

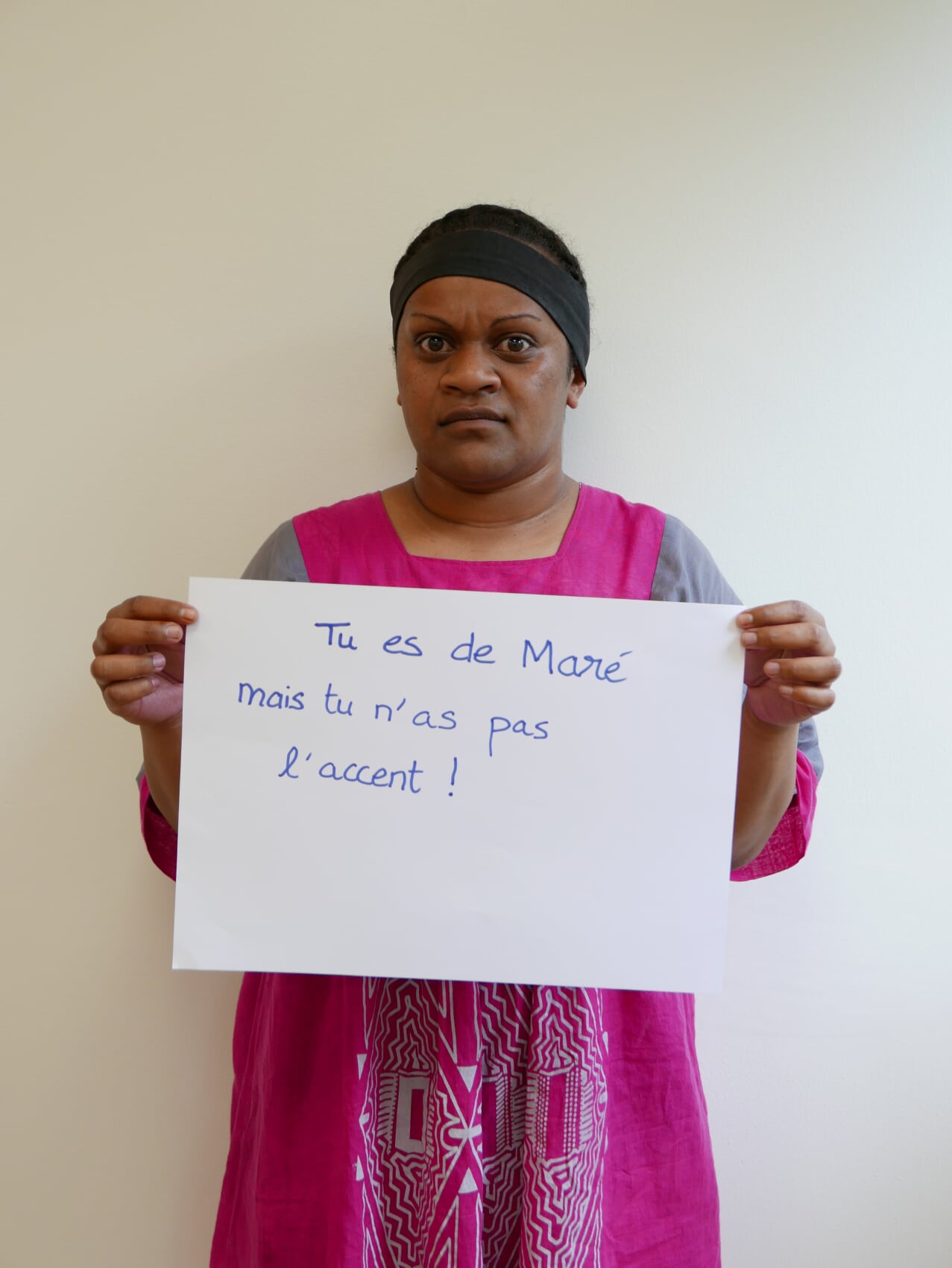

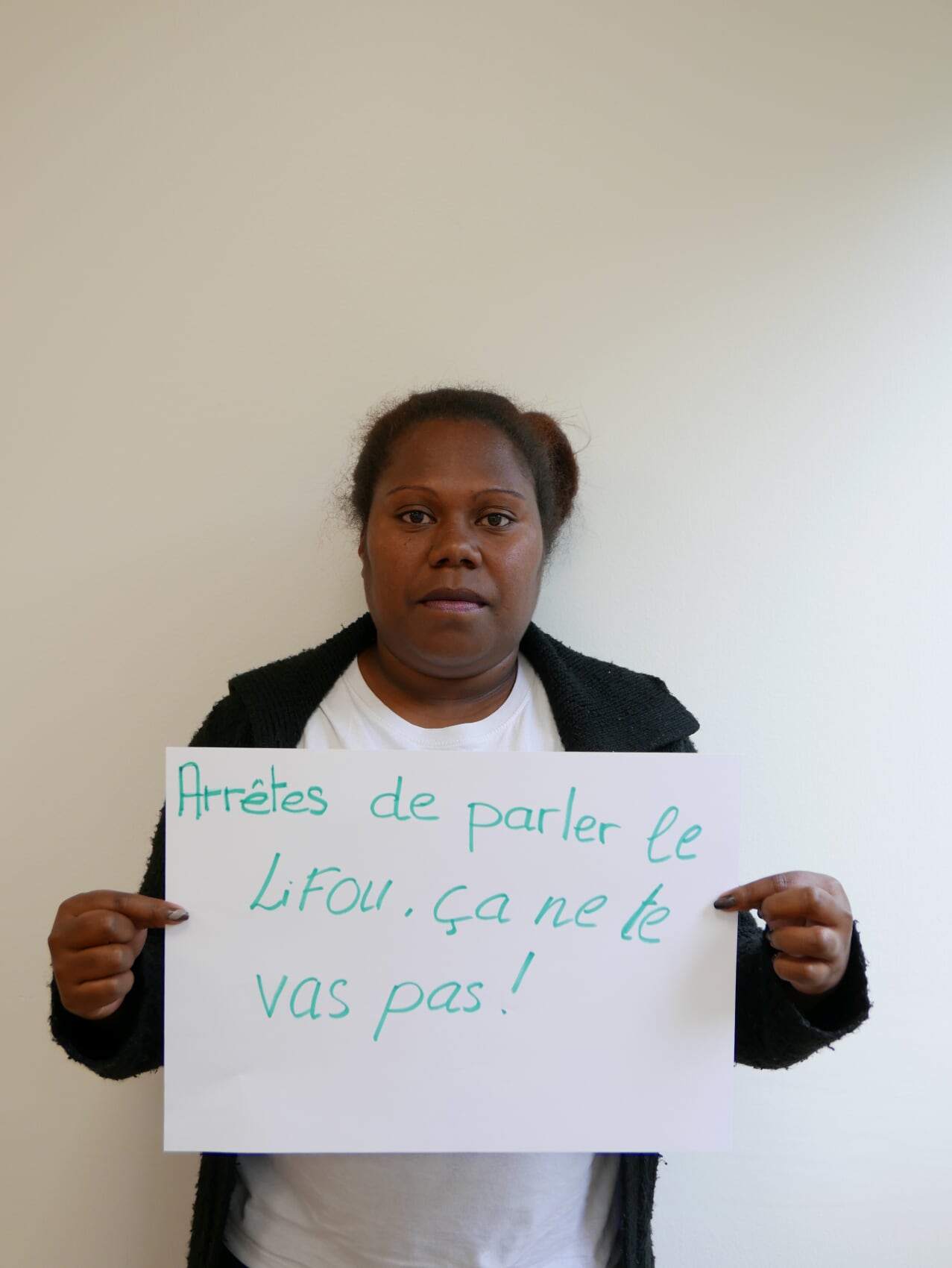

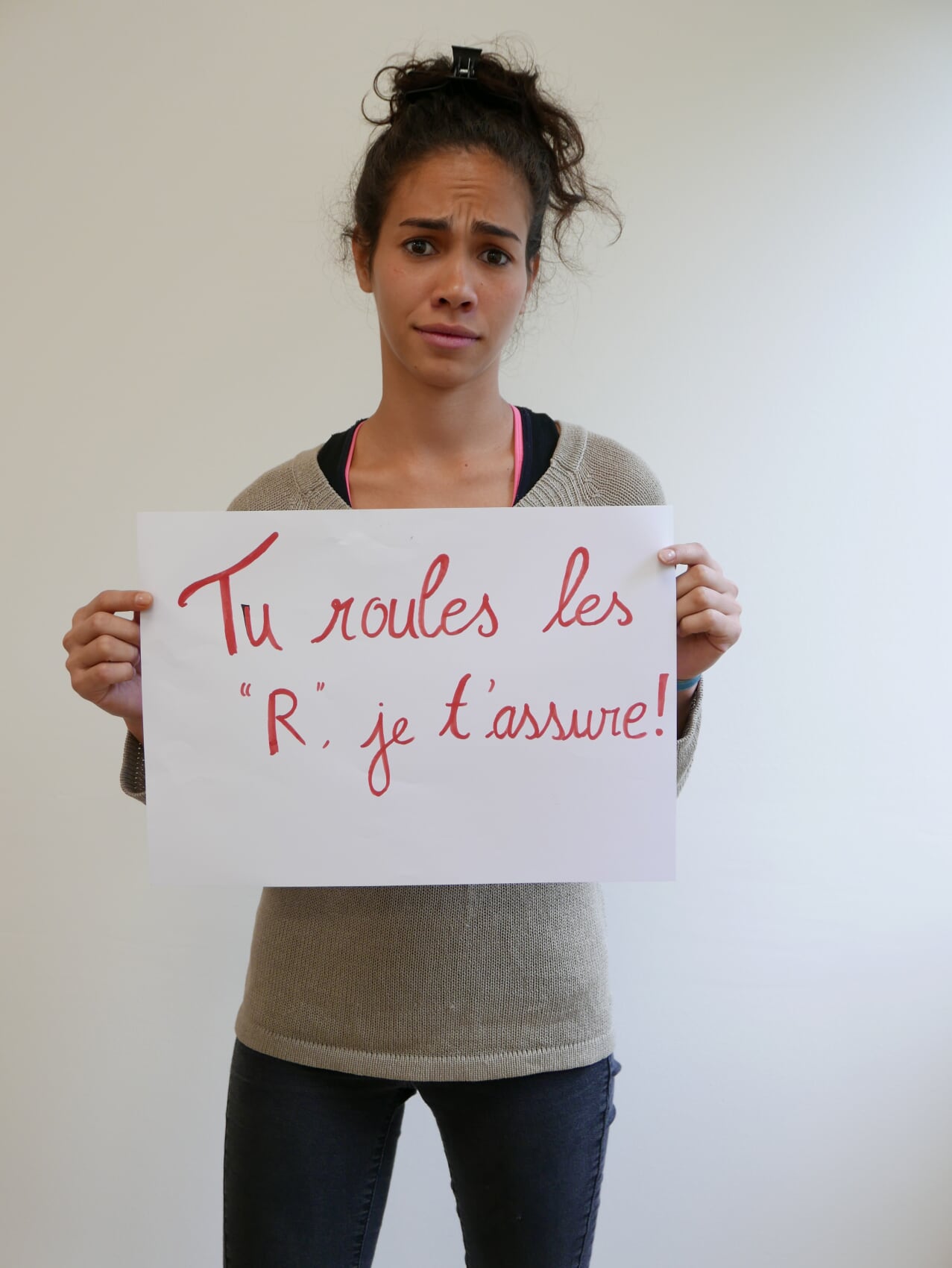

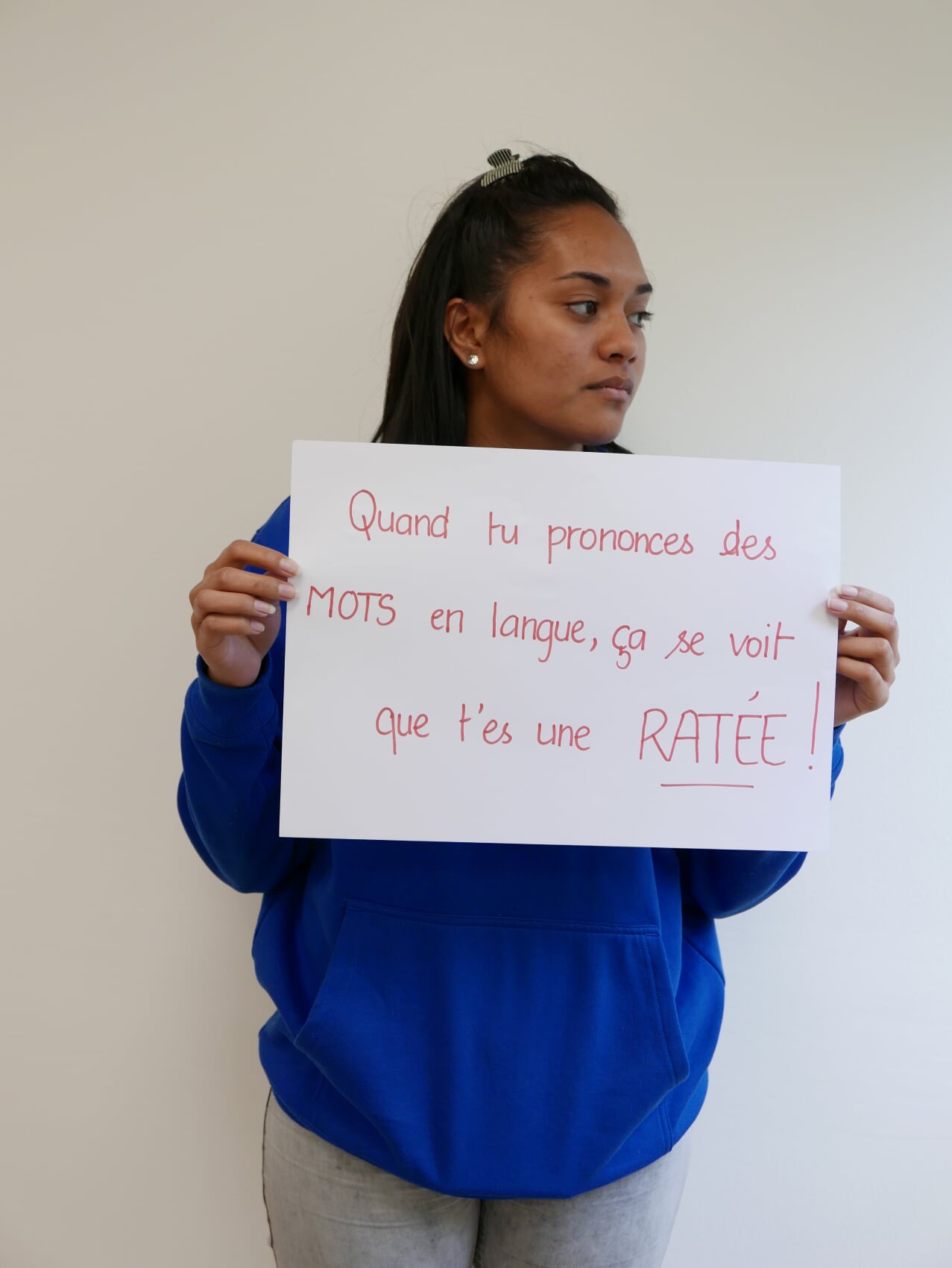

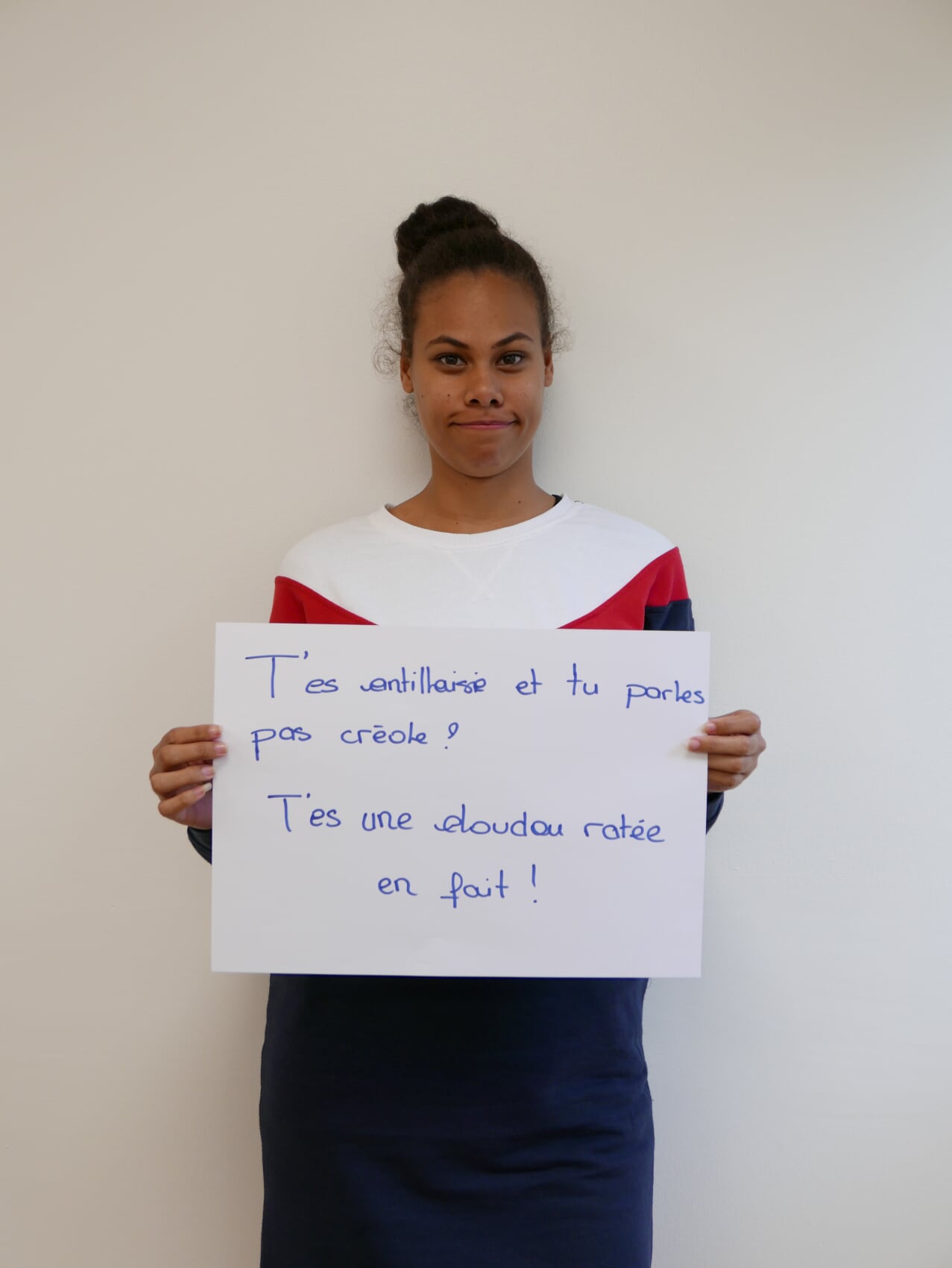

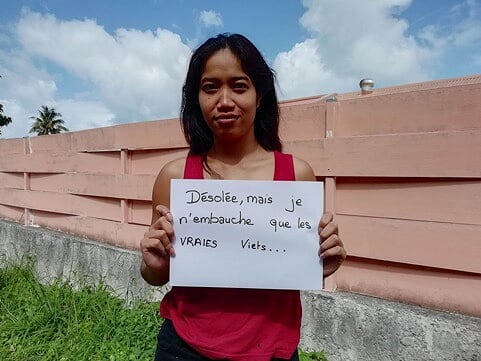

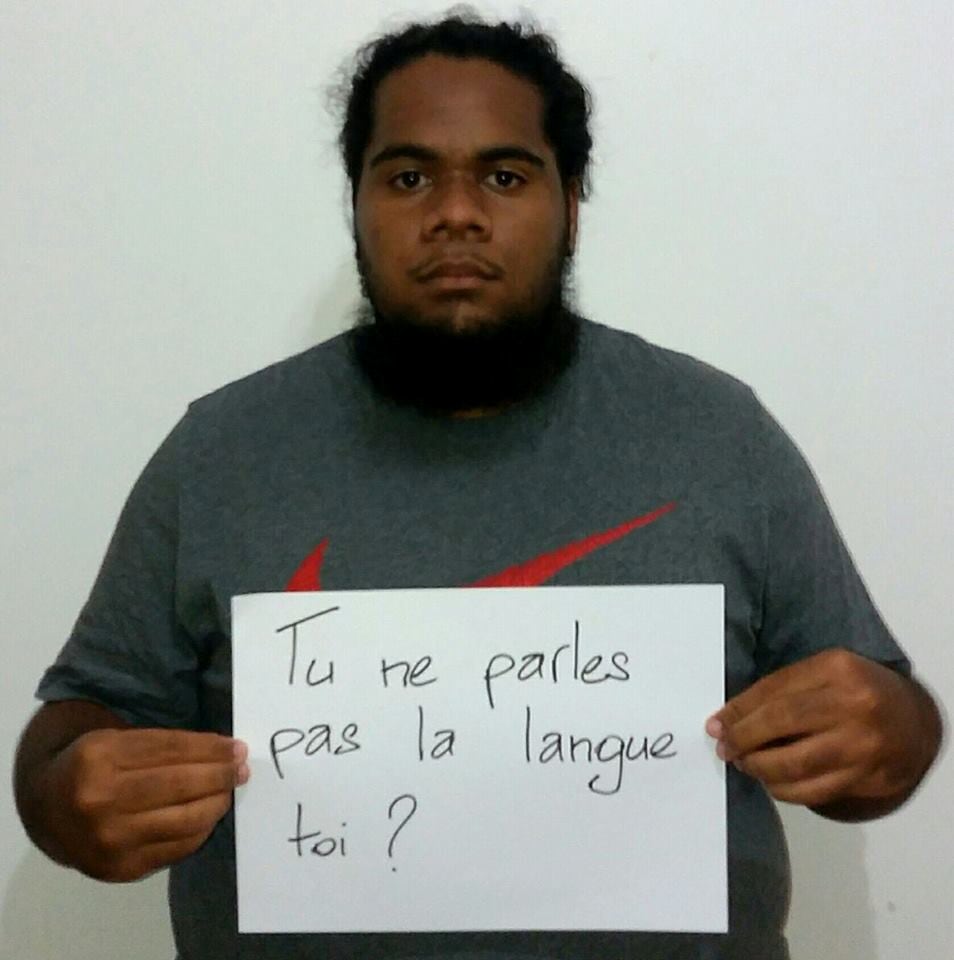

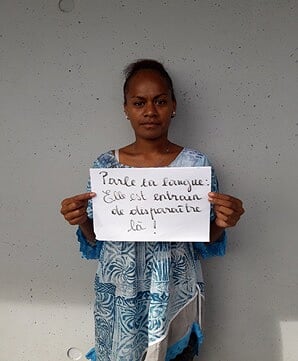

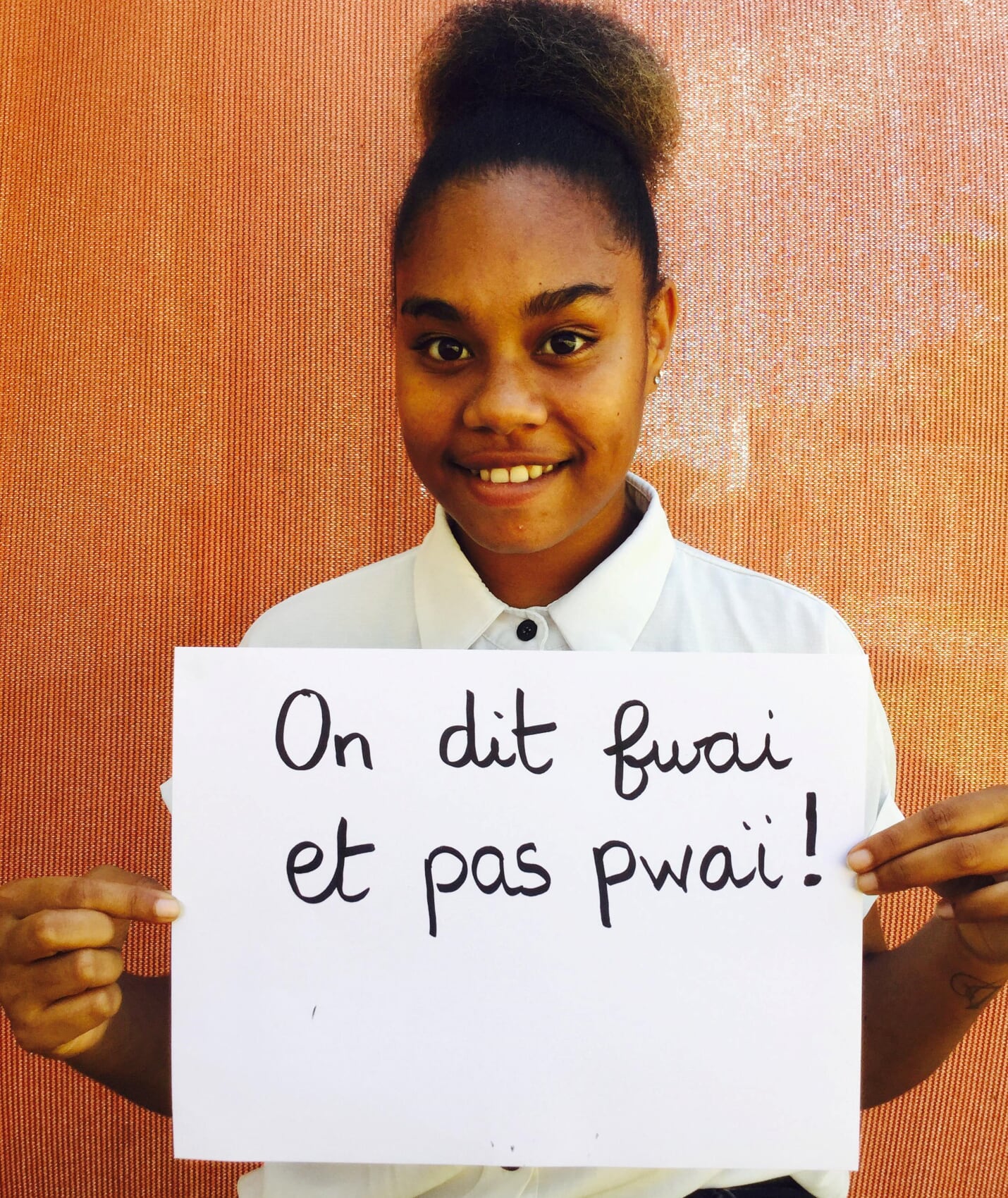

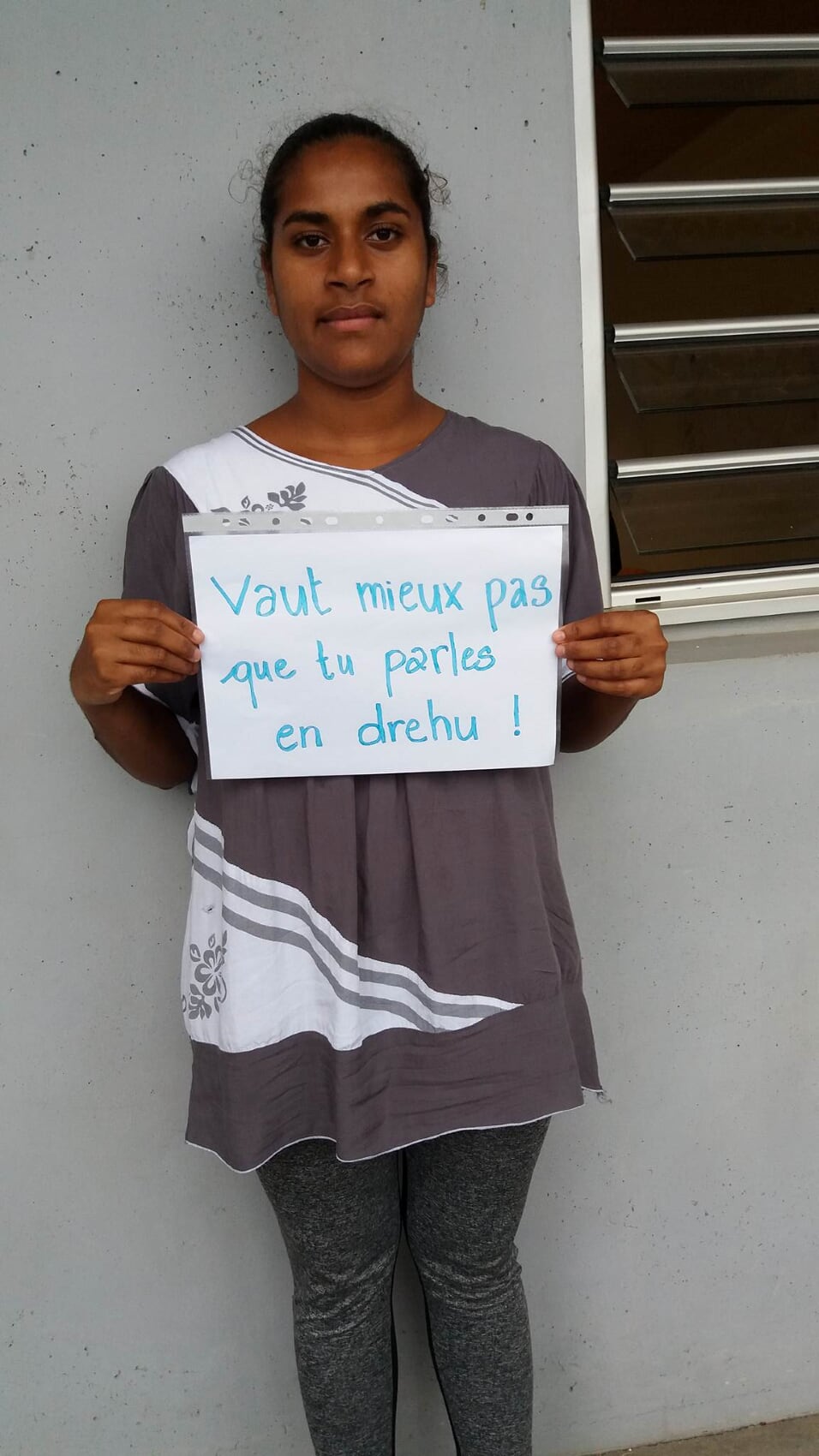

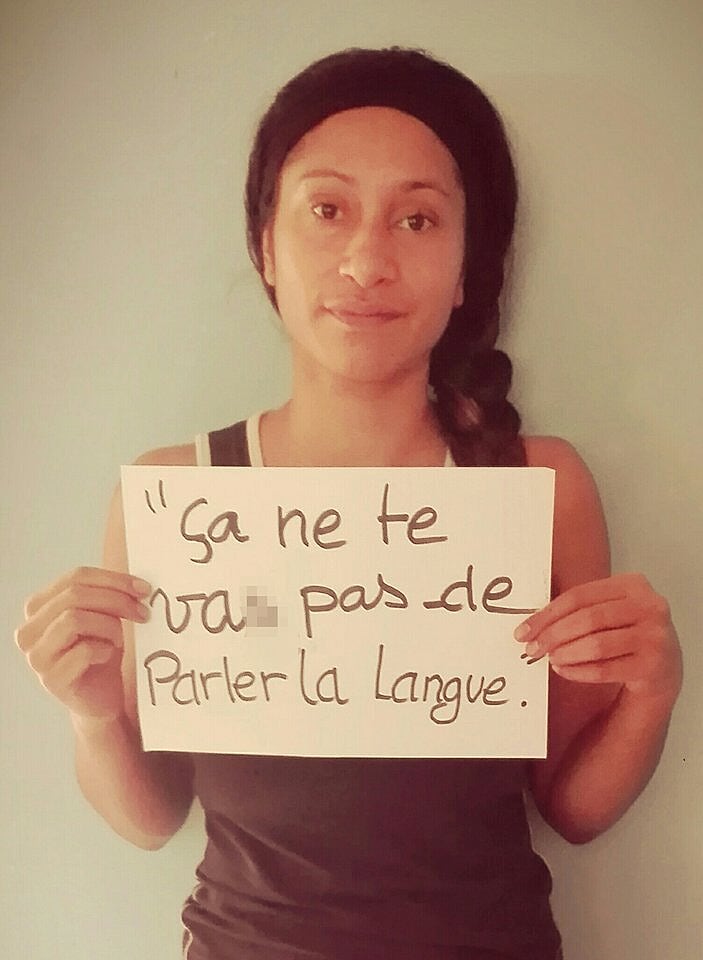

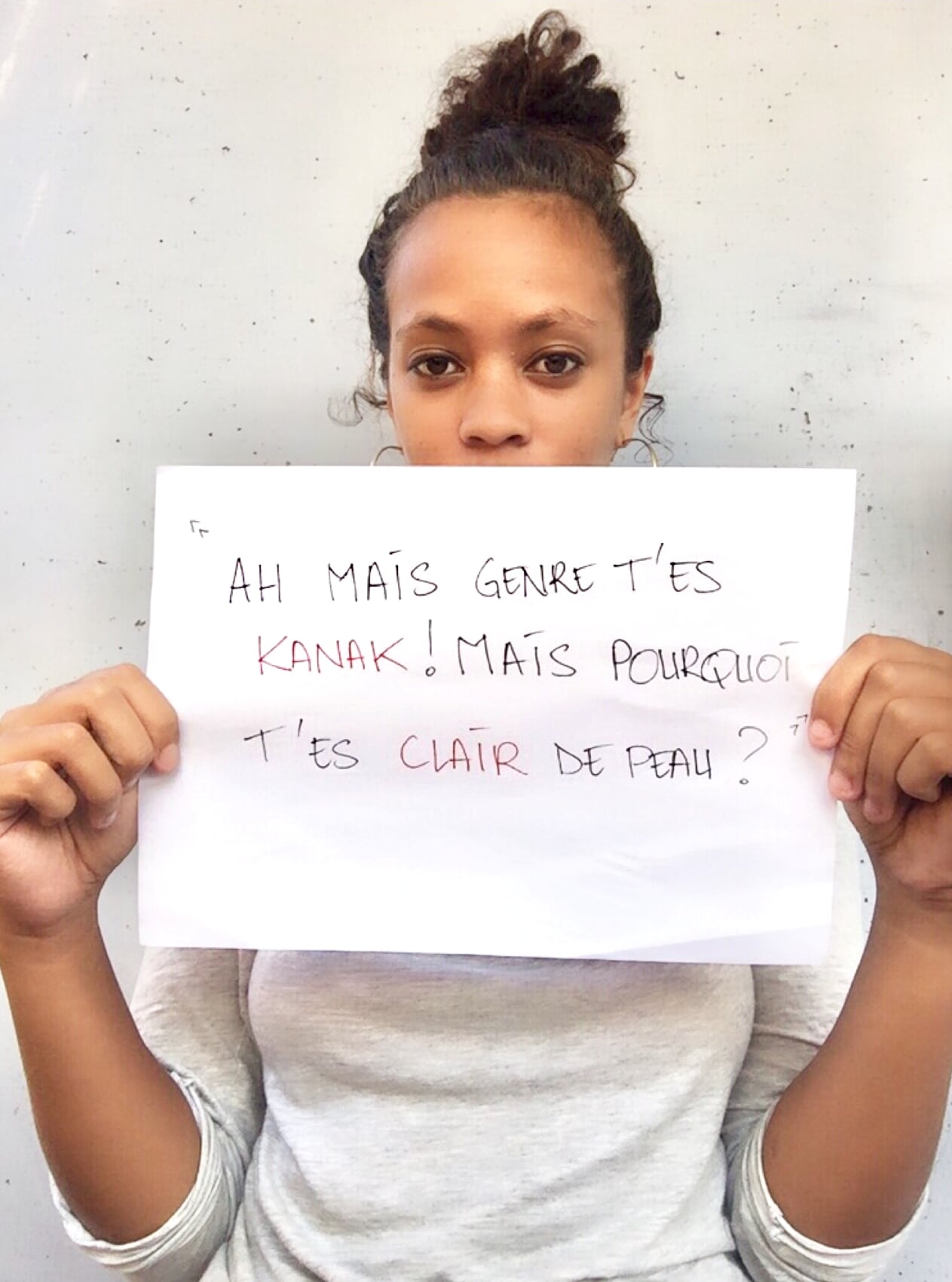

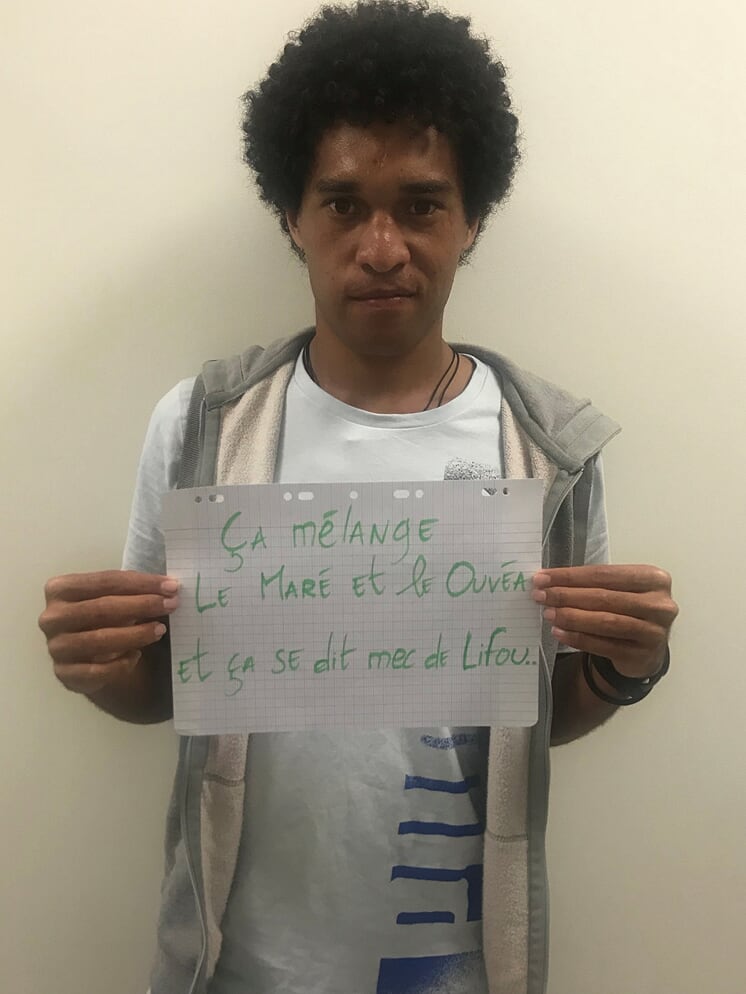

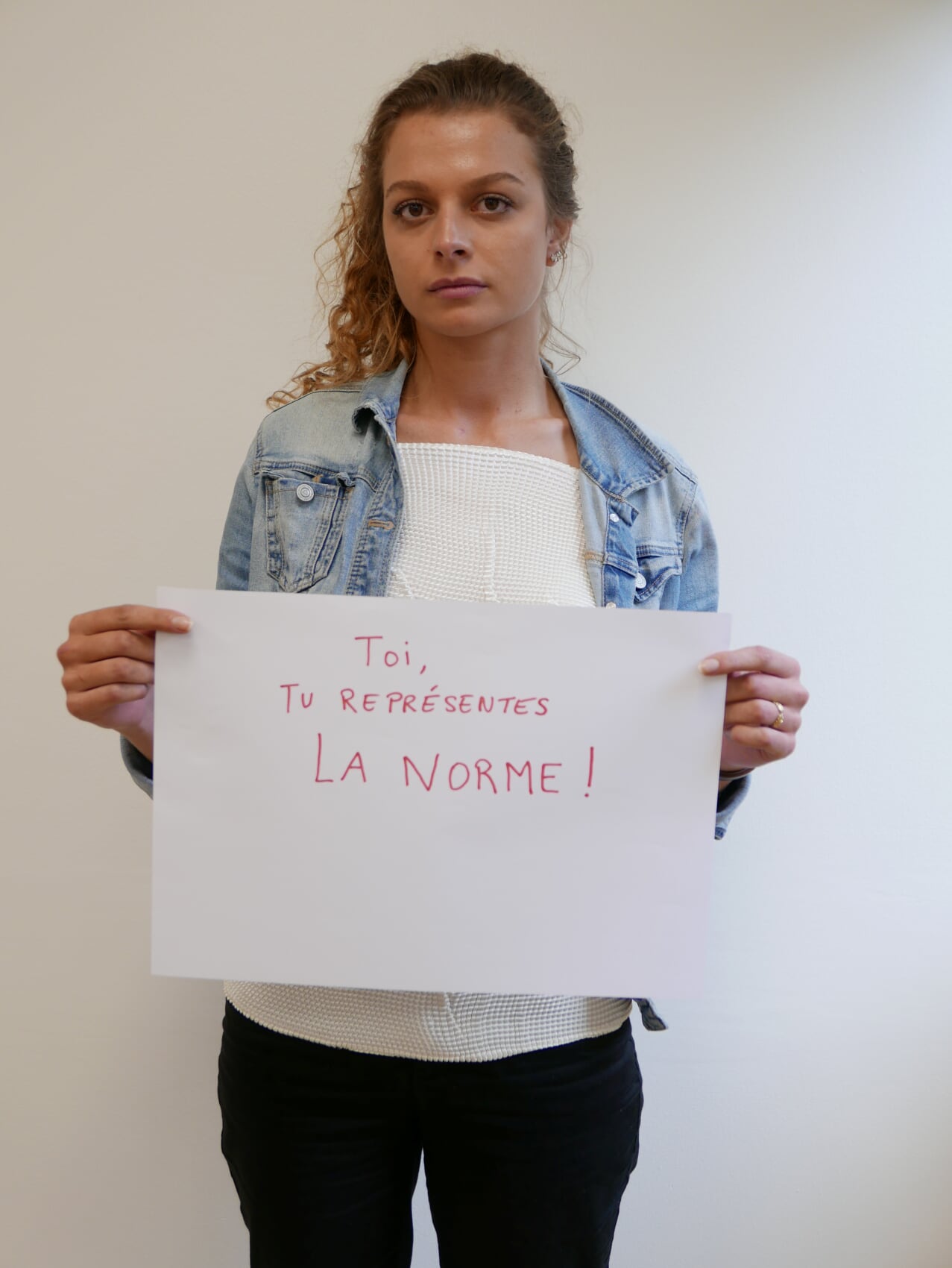

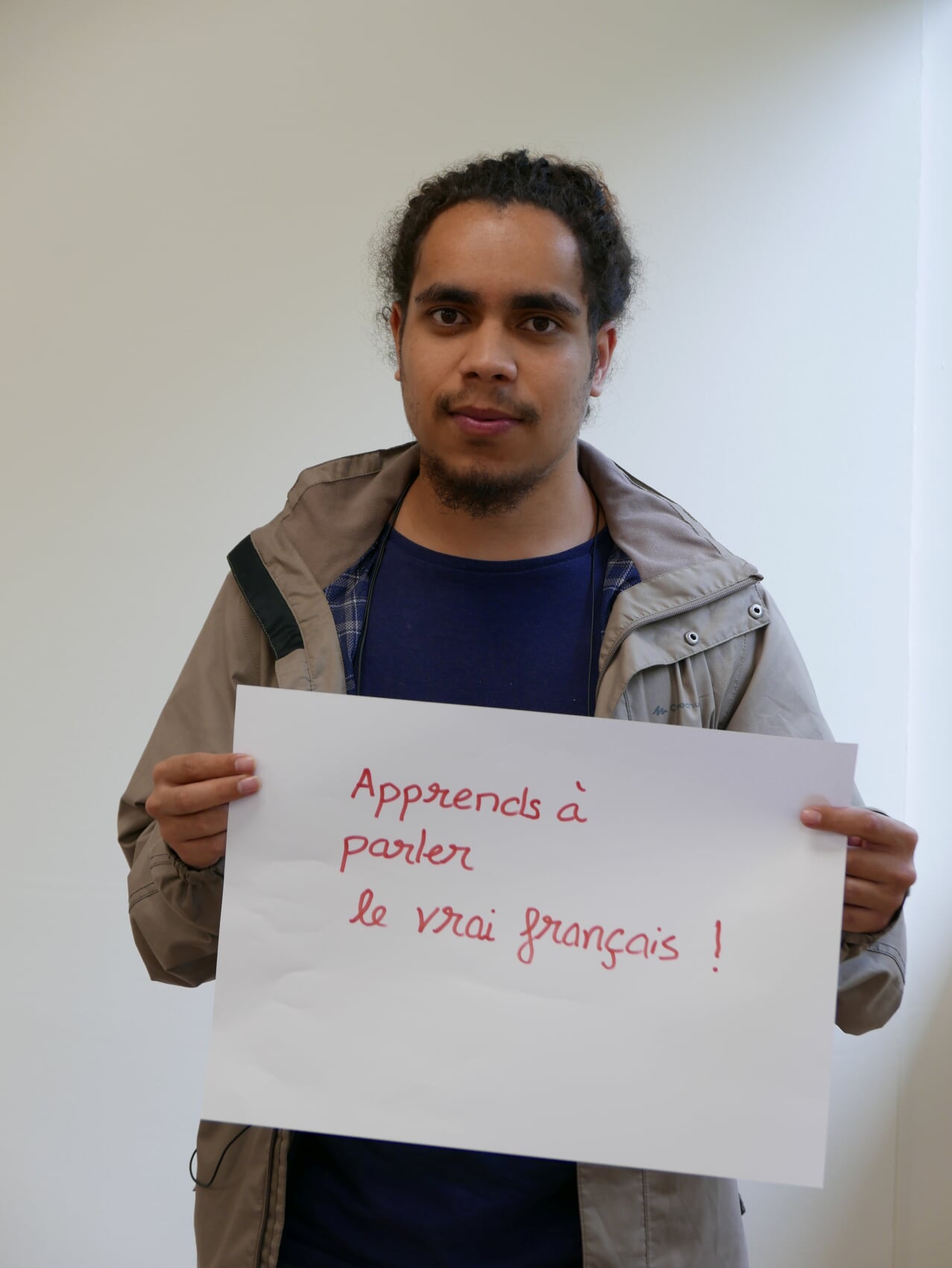

Specialising in sociolinguistics, Dr Elatiana Razafi and linguistics for Dr Fabrice Wacalie, asked their students to think of ‘linguistic micro-aggressions’ they experienced. Students were then invited to take self-portraits with the transcript of the micro-aggression and to share the story behind it.

‘We weren’t sure if they would be responsive and were even less able to predict the outcomes. But as the students sent in their work, we realized how much there was to learn from their visual narratives’, Dr Razafi and Wacalie reflected. Exploring the issue through a combination of visual anthropology and street art, they had two objectives in mind:

- learn more about the linguistic norms that shun Caledonia’s youth today and raise public awareness on the realities of linguistic micro-aggressions;

- empower young plurilingual Caledonians through artistic promotions of linguistic diversity.

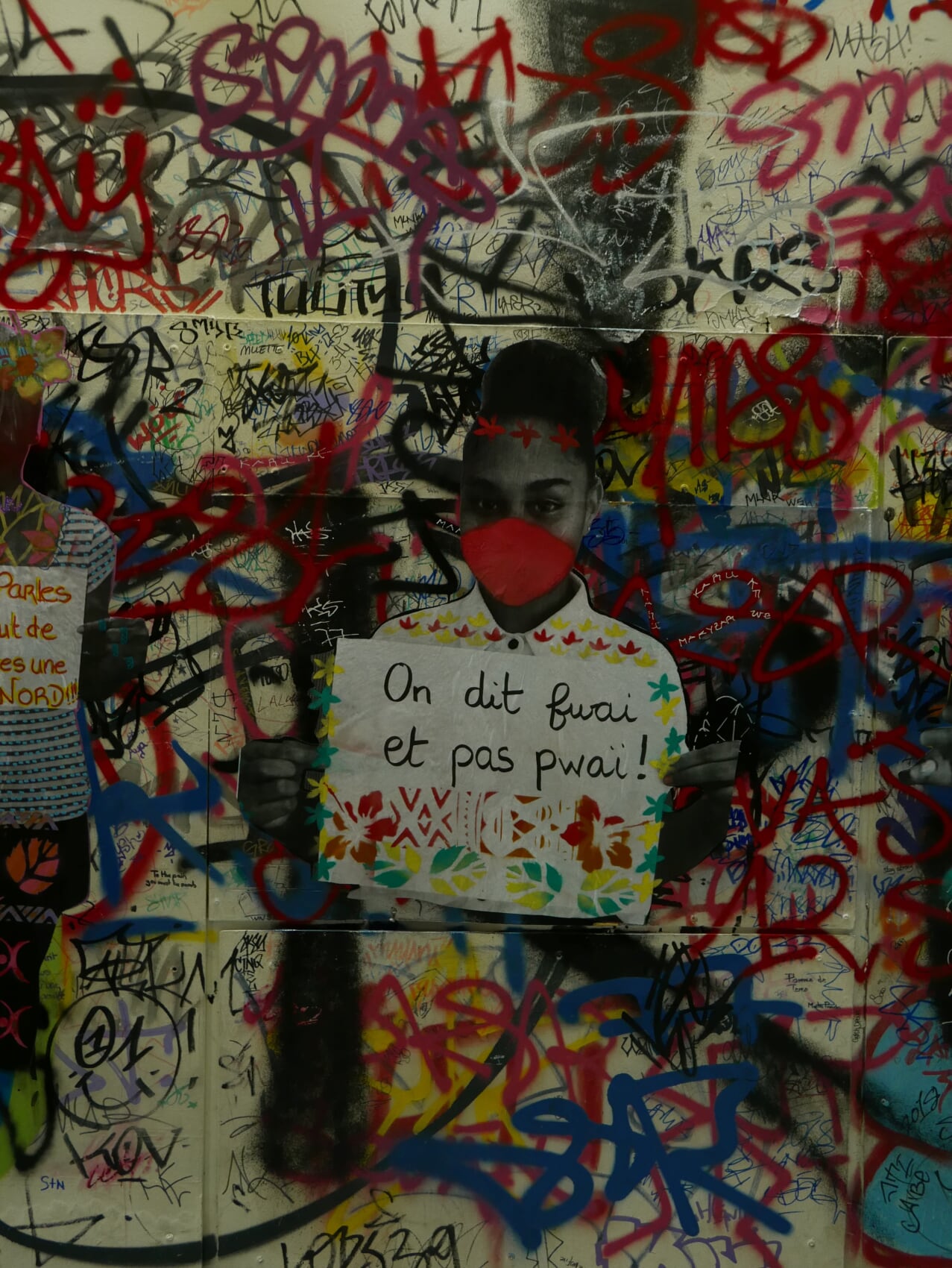

Firstly, the pictures show how monolinguistic ideologies (pressure to speak only French) and mononormative (pressure to speak it a certain way) produce everyday linguistic violence. This type of micro-aggression is interlinguistic as it opposes different linguistic communities.

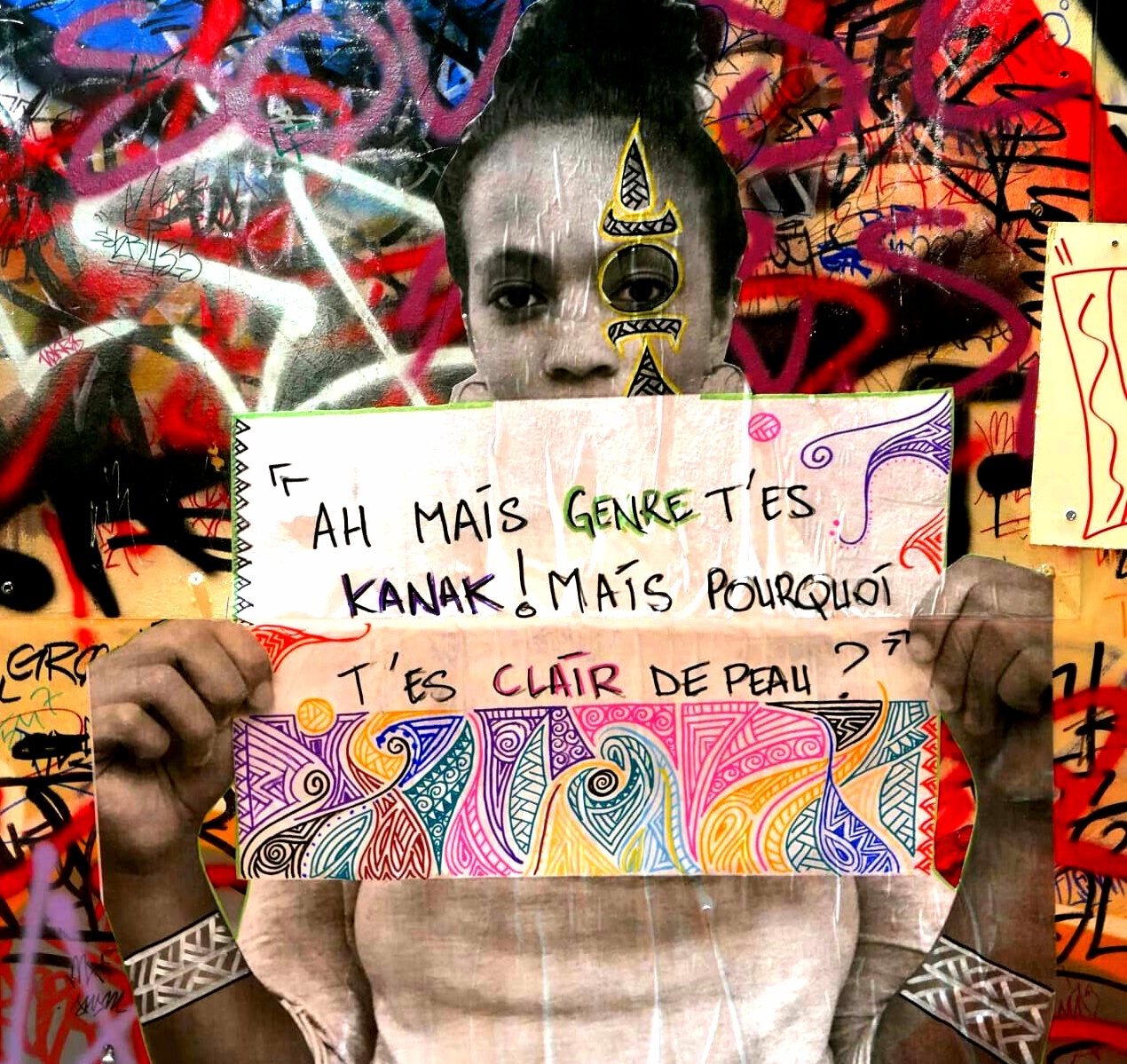

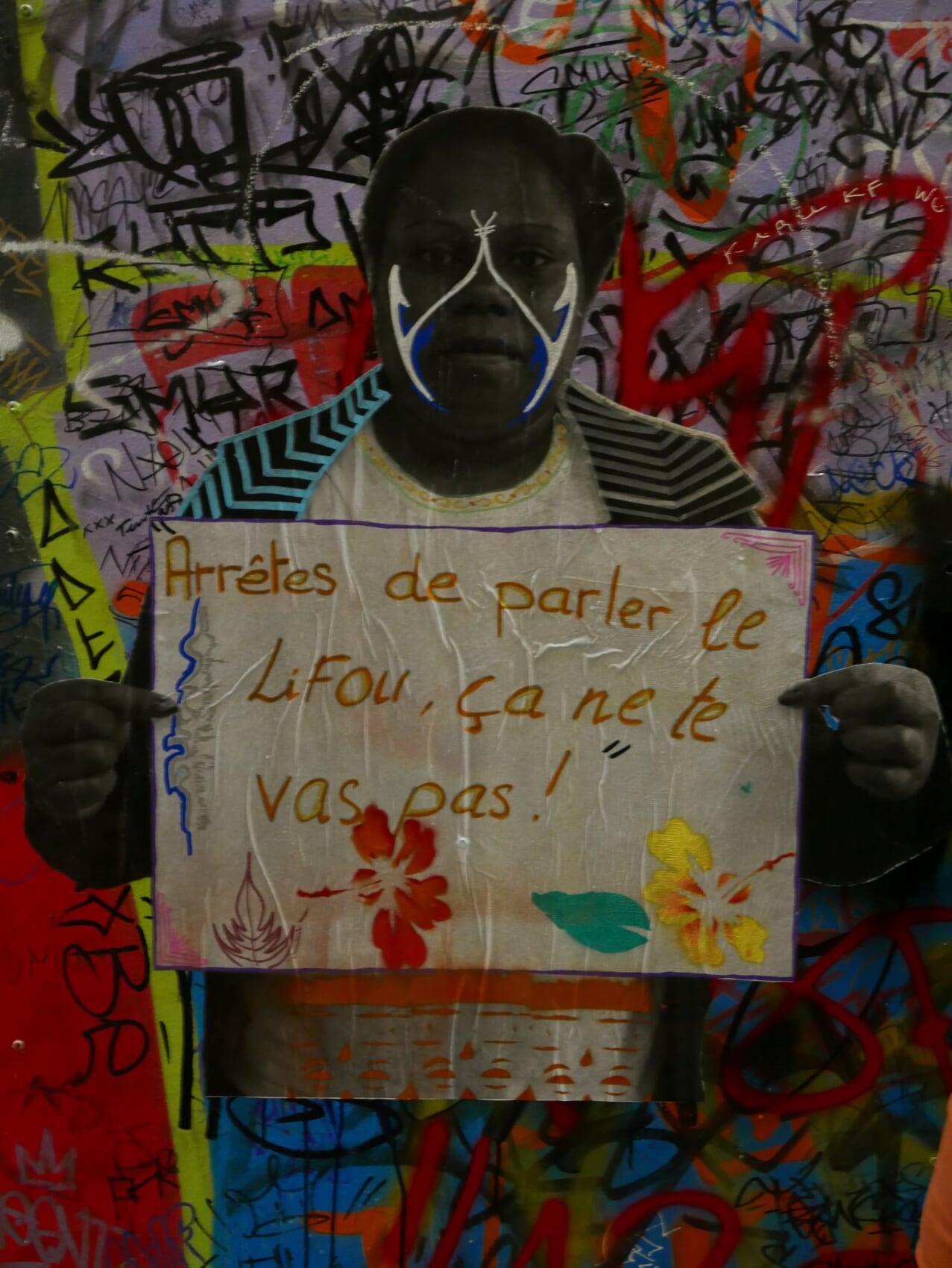

GALLERY 1: Interlinguistic micro-aggressions

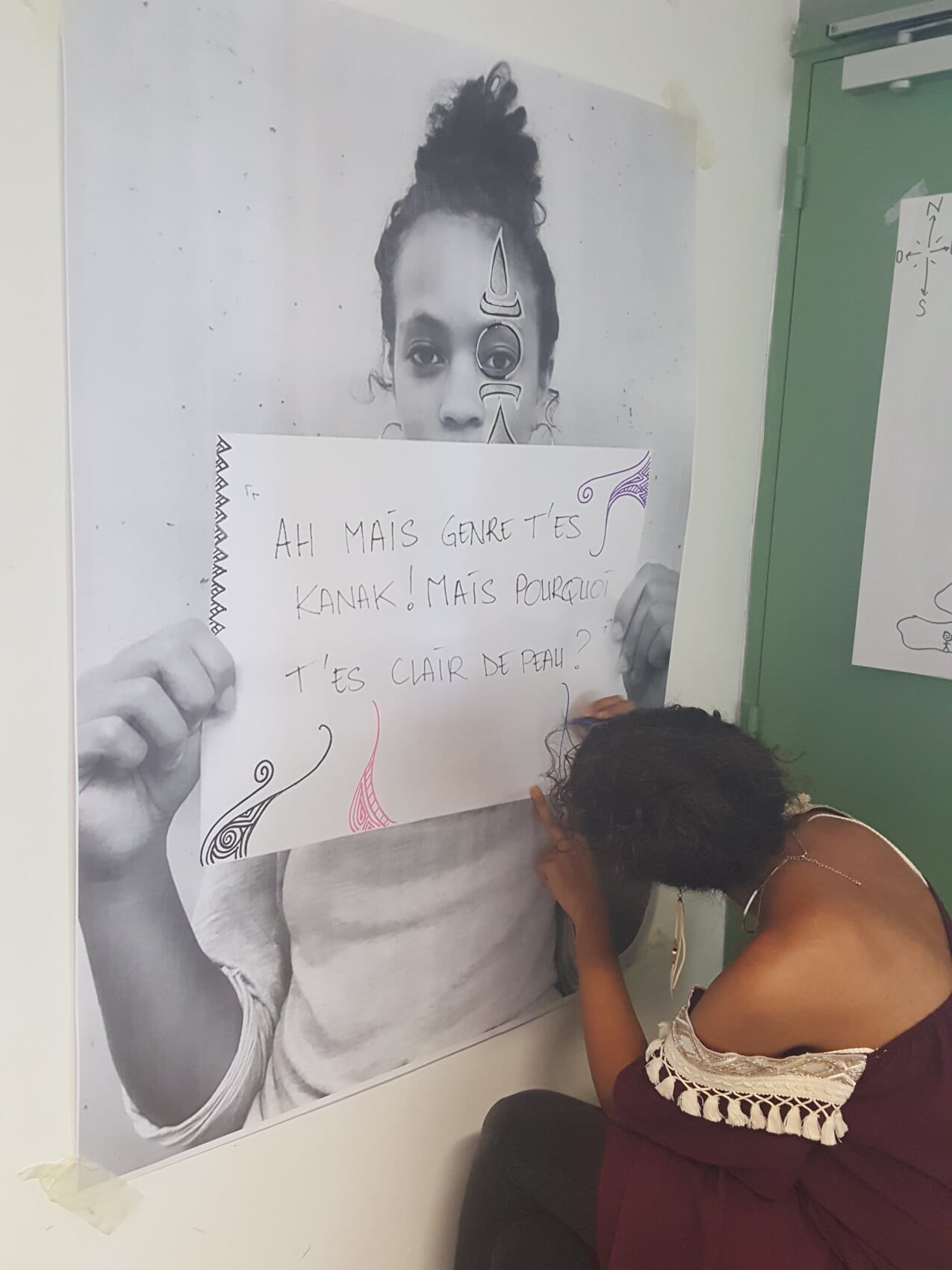

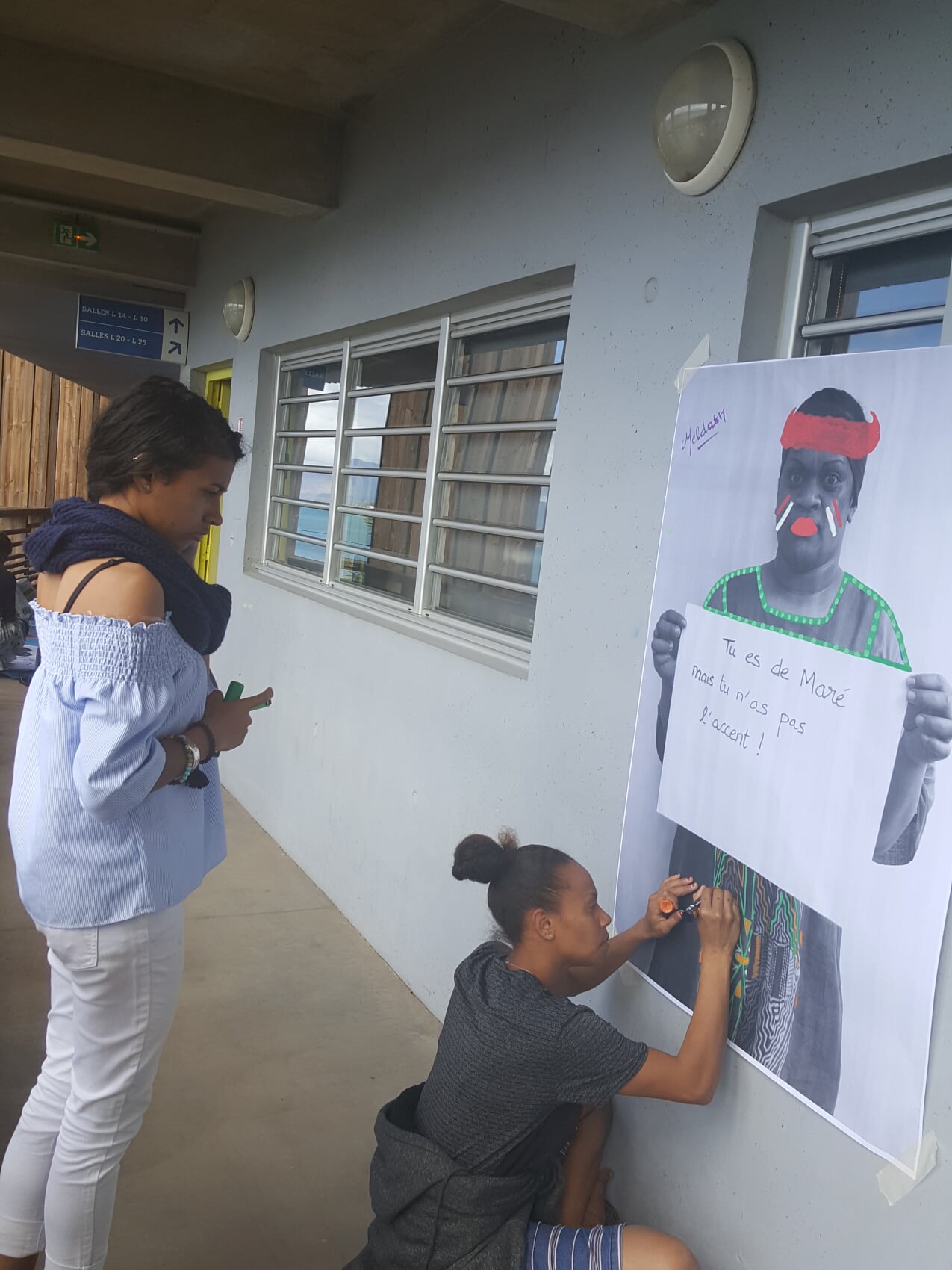

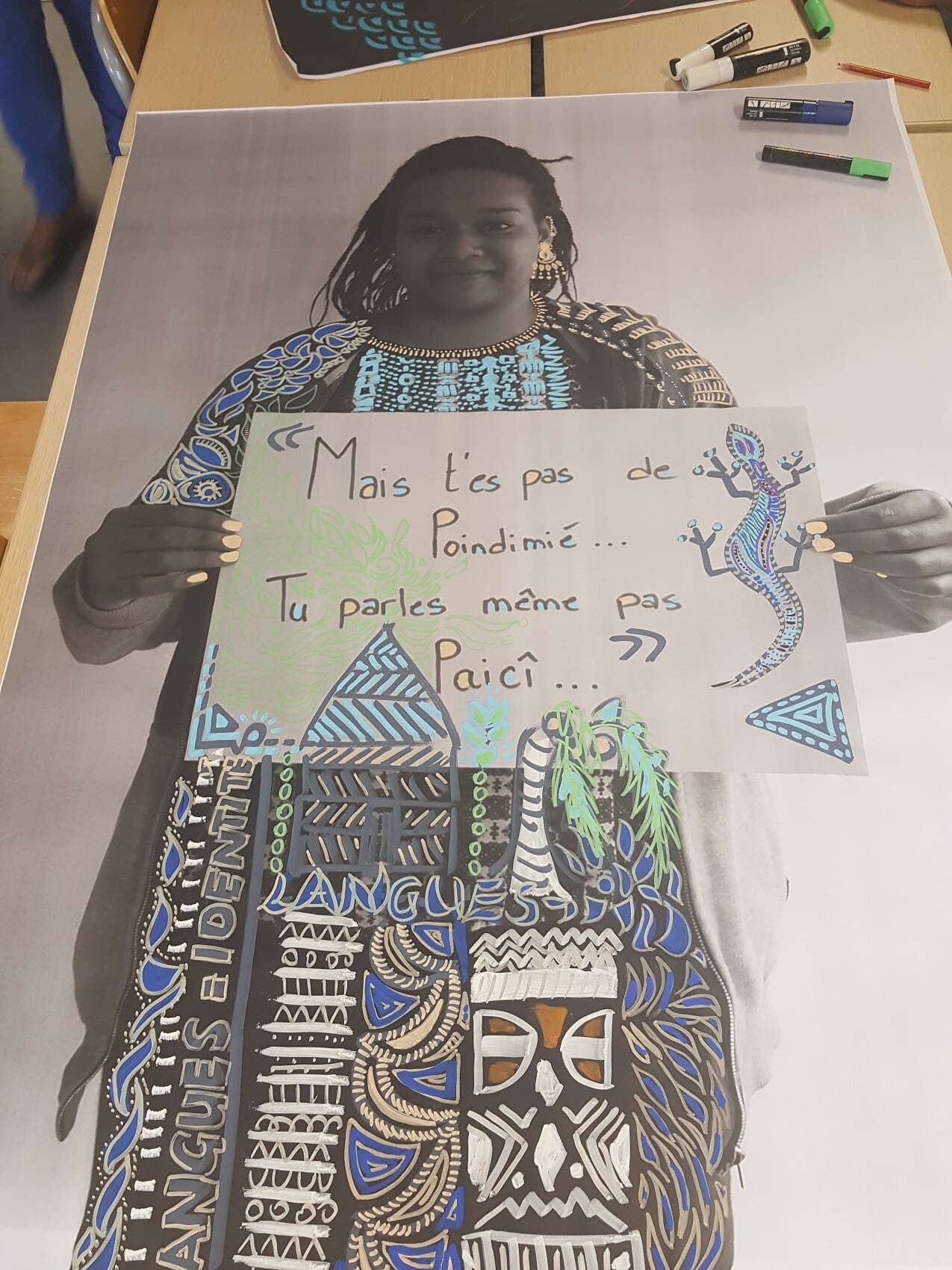

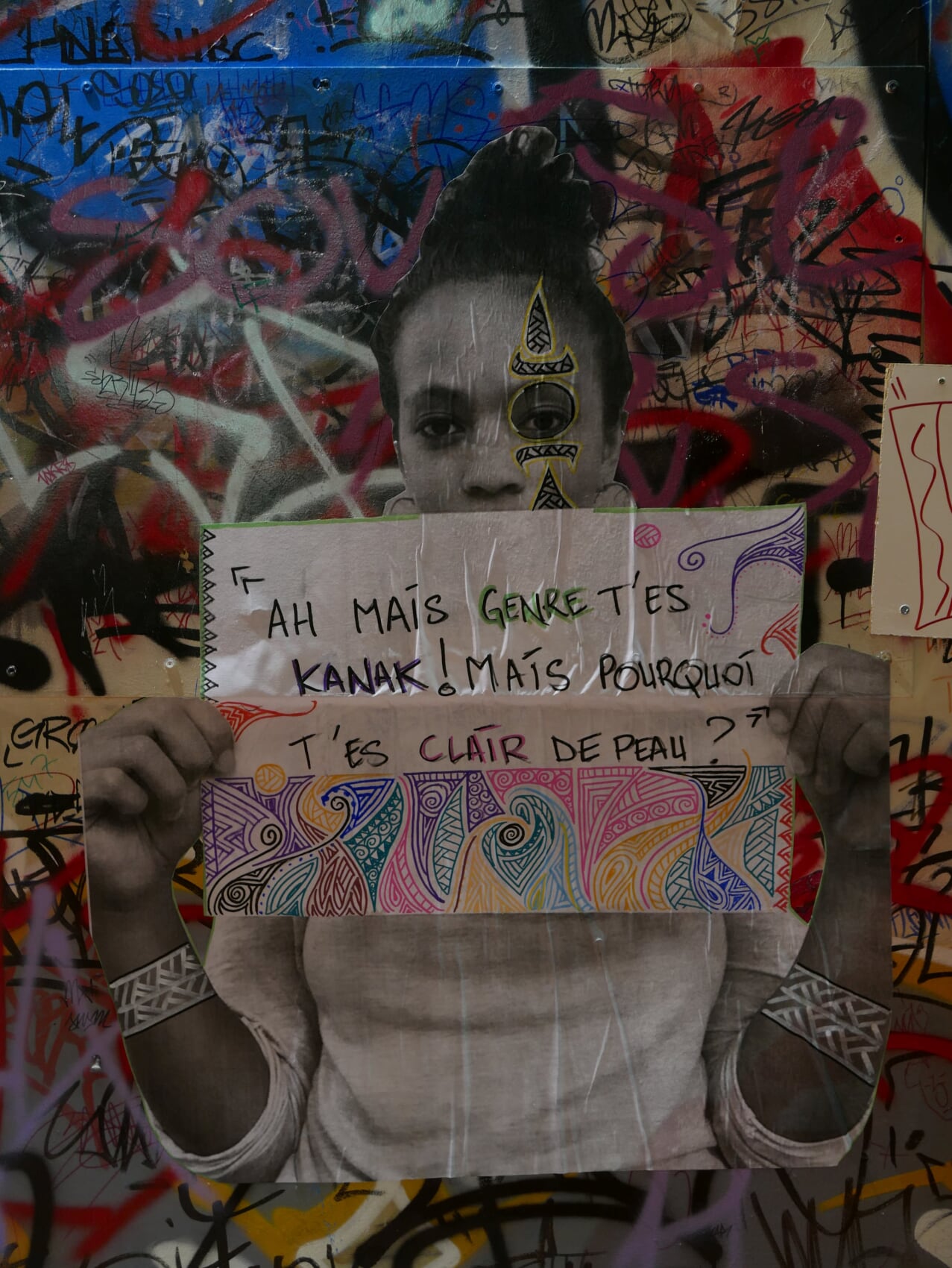

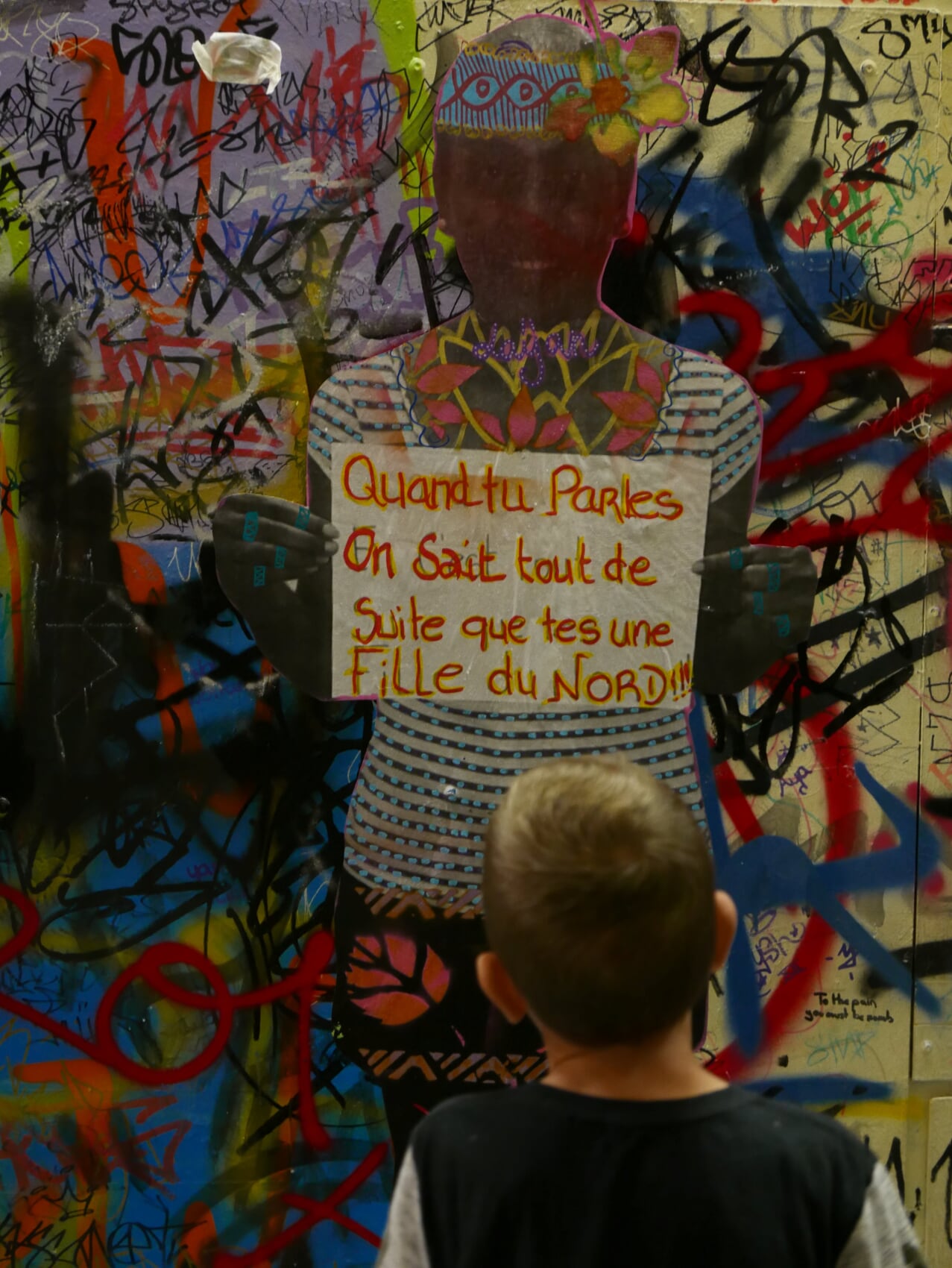

Secondly, the students’ stories brought attention to the weight of intralinguistic pressure, i.e. micro-aggressions carried out internally within a linguistic community. Whether at home, amongst their families or at school, they tell us how they have been the target of contradictory imperatives since their childhood.

In the case of some Kanak students, the elderly in their tribes expect them to speak ‘indigenous’ languages: ‘Speak our language: it is disappearing!’; ‘You don’t speak your own language?!’ At the same time, they are mocked when they do so. Some are even refused the right to speak a Kanak language: ‘It doesn’t suit you to speak our language’; ‘You’re better off not speaking drehu’.

Their pronunciation, the fact they also speak French or their skin colour are amongst the features usually held against them, questioning their legitimacy to be a fully acknowledged speaker i.e. a ‘real’ community member.

GALLERY 2: Intralinguistic micro-aggressions

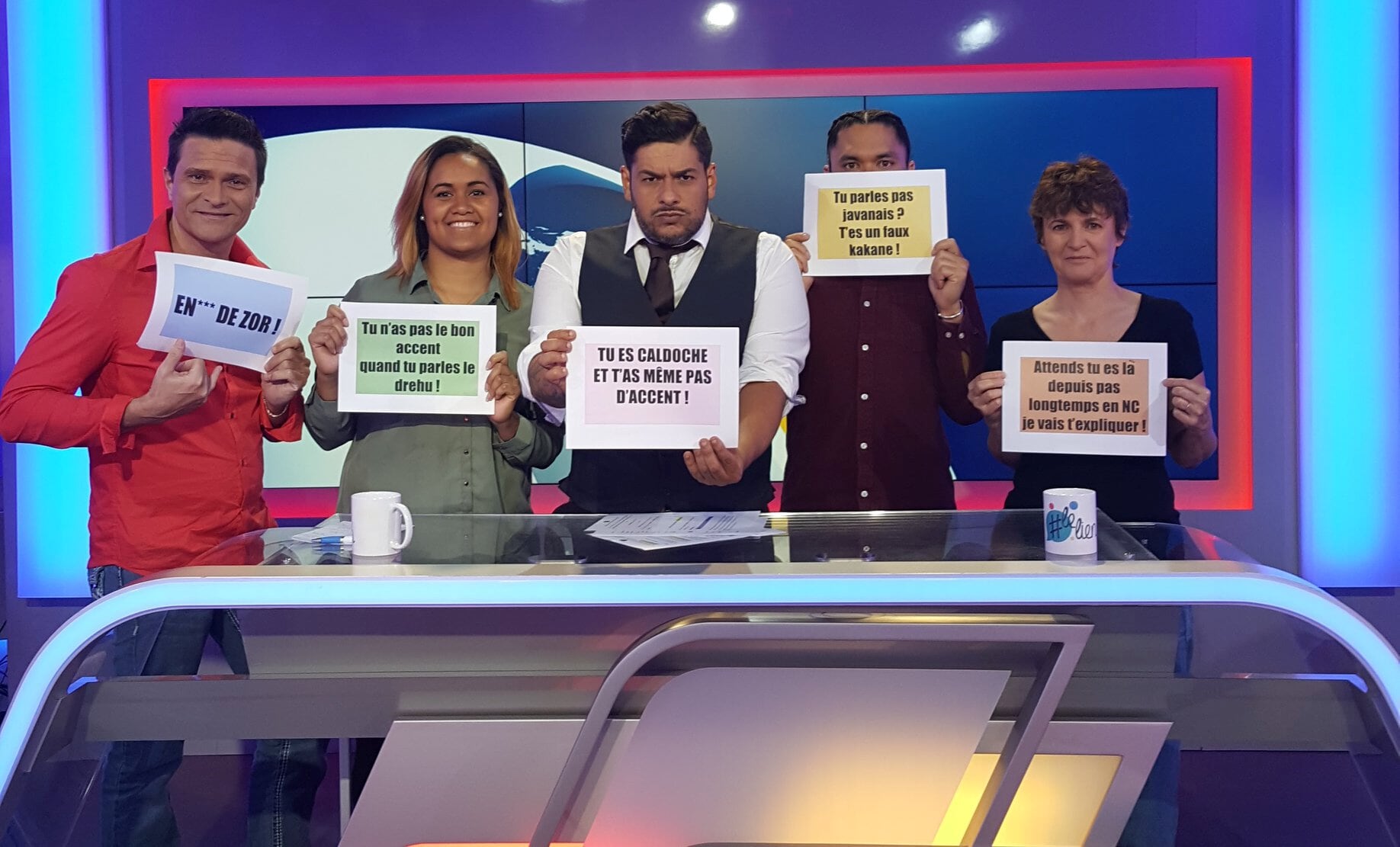

The project also revealed that linguistic micro-aggressions are borderless. It is not only the speakers of minority languages that experienced discrimination. Students who are associated with the ‘dominant’ social group of ‘whites’ and ‘French-speakers’ have also had to face up to linguistic insults. In this case, they can be stigmatized because of their alleged monolingualism.

GALLERY 3: Micro-aggressions are borderless. Members of the supposedly dominant ‘white’ and ‘French’ community are also in turn concerned

The discussions in class then made obvious the need to raise awareness – beyond the classroom walls – on the disturbing extent of linguistic discrimination as well as on the benefits of linguistic diversity. The visual narratives gathered throughout the project ended up becoming creative means for self-empowerment. Upon discovering one another’s stories, each student felt less isolated with their experiences of discrimination based on their languages. Altogether, they became less shameful and were eager to counter act their linguistic micro-aggressions.

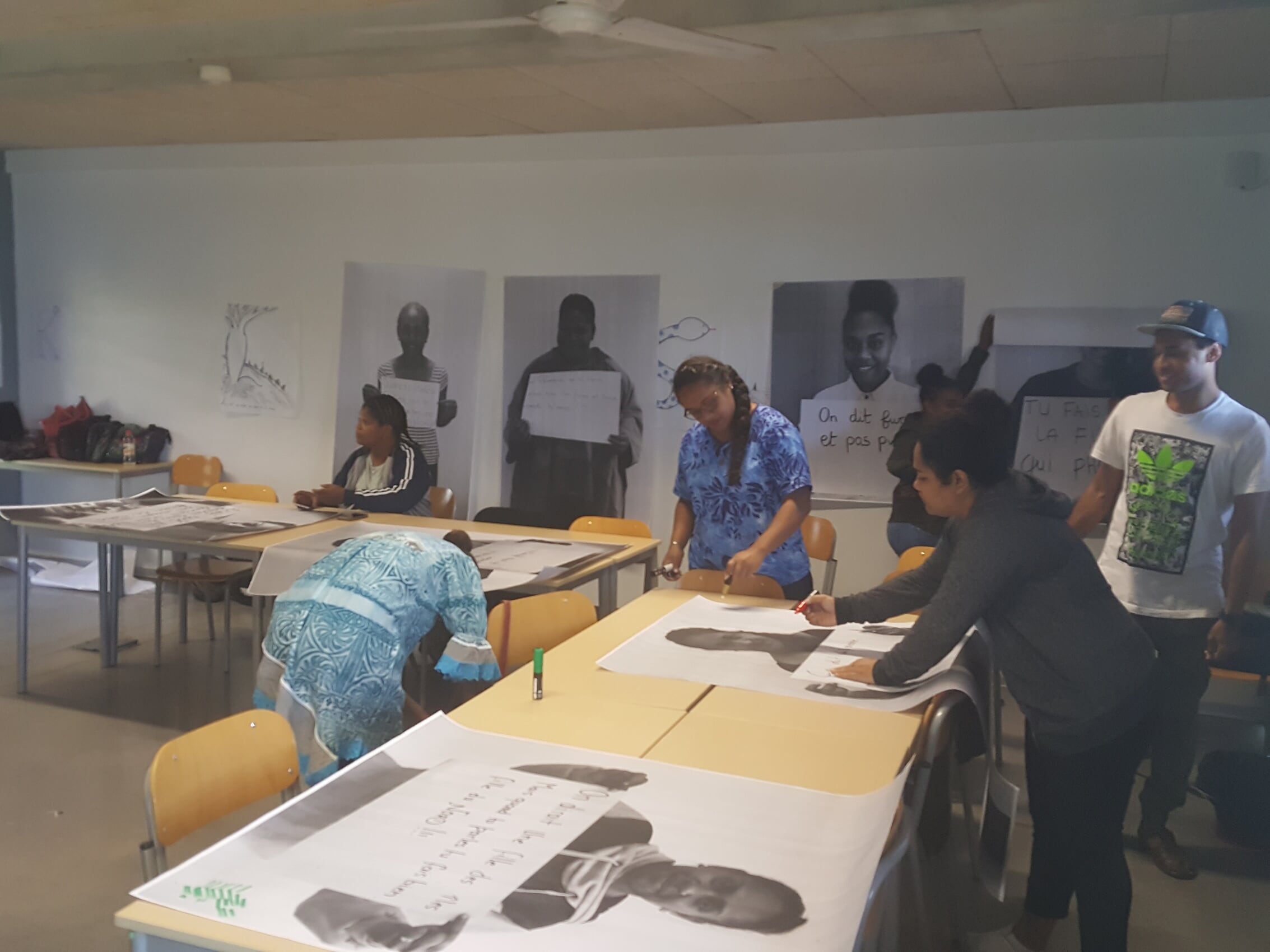

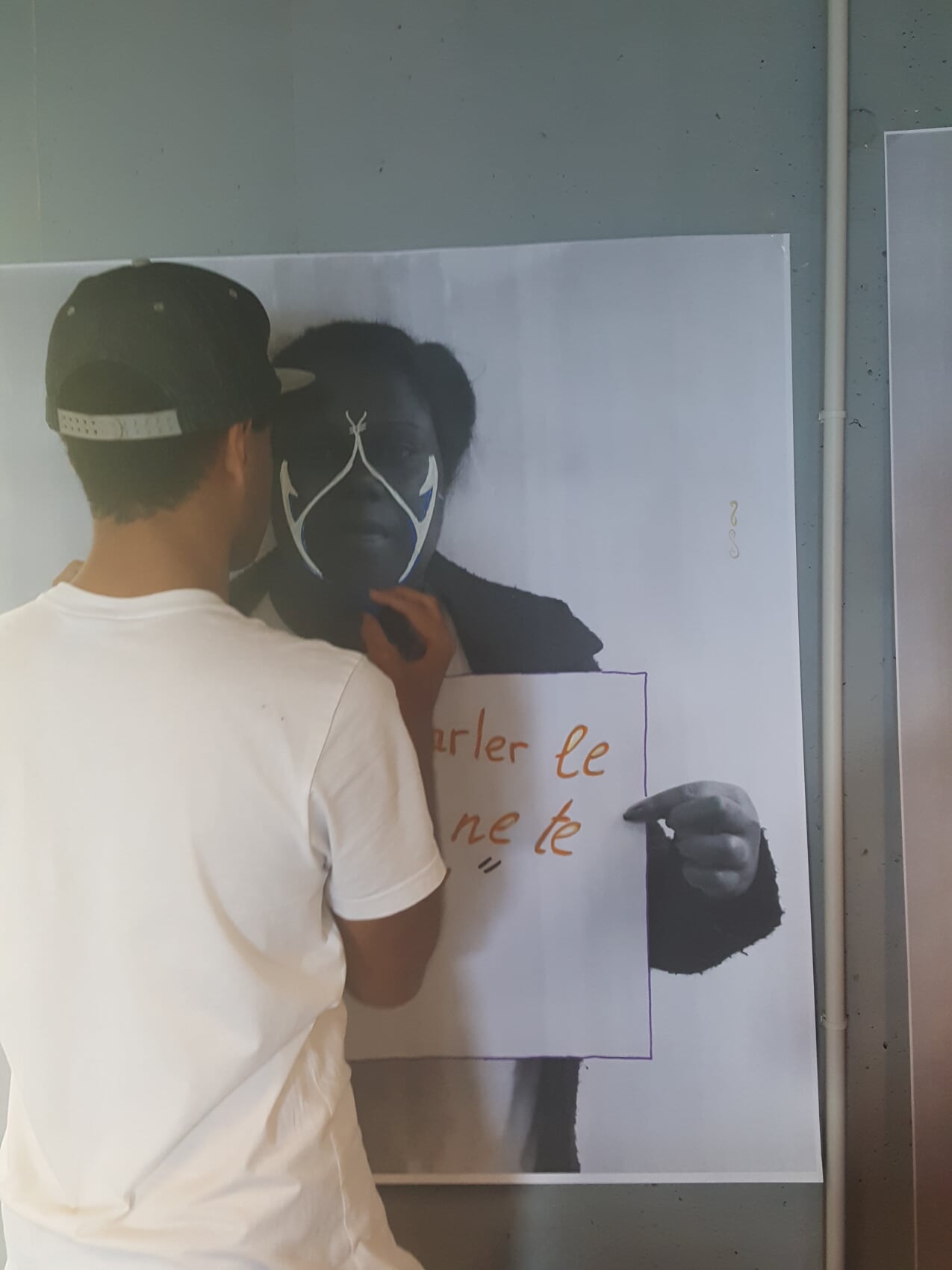

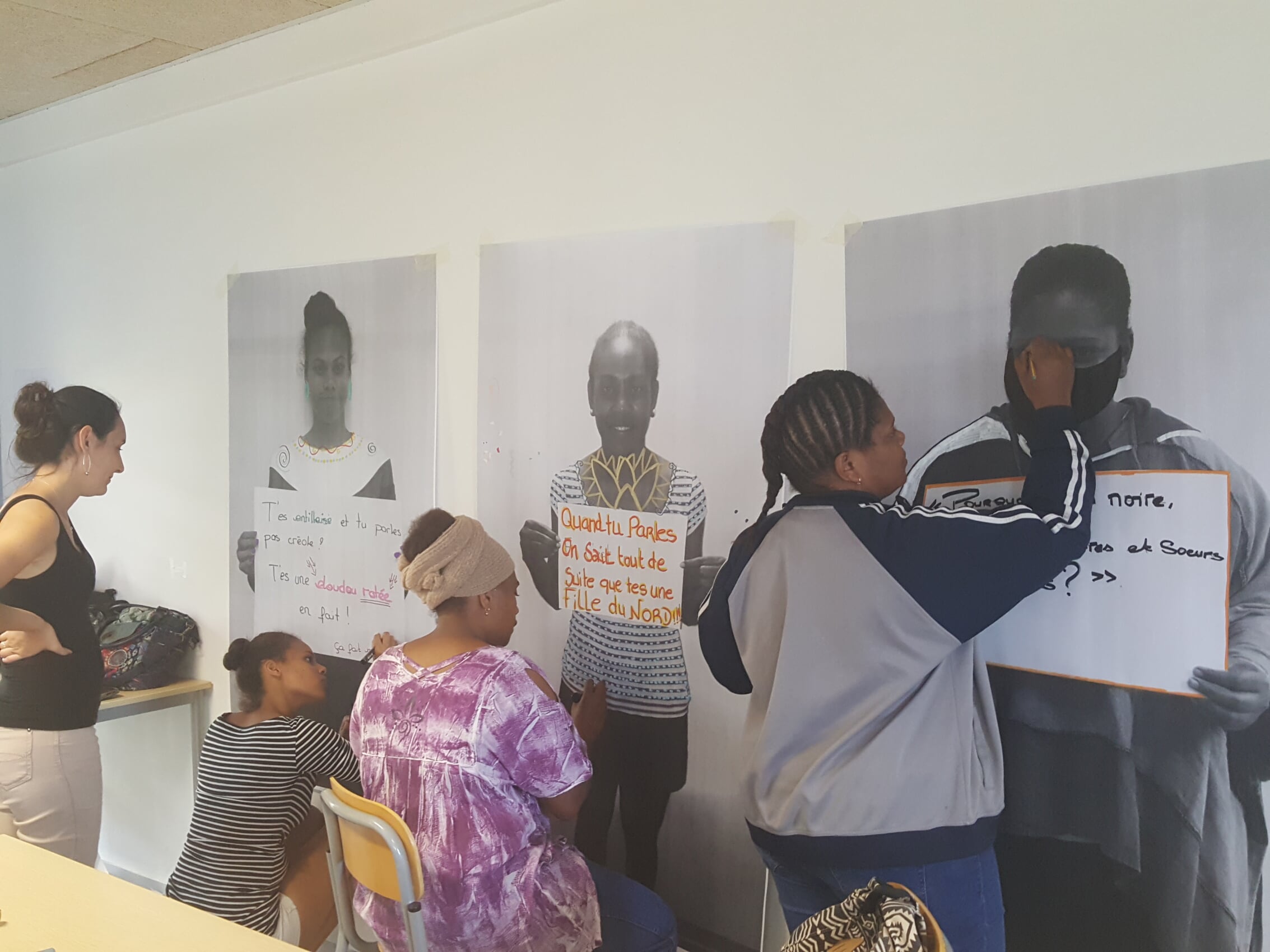

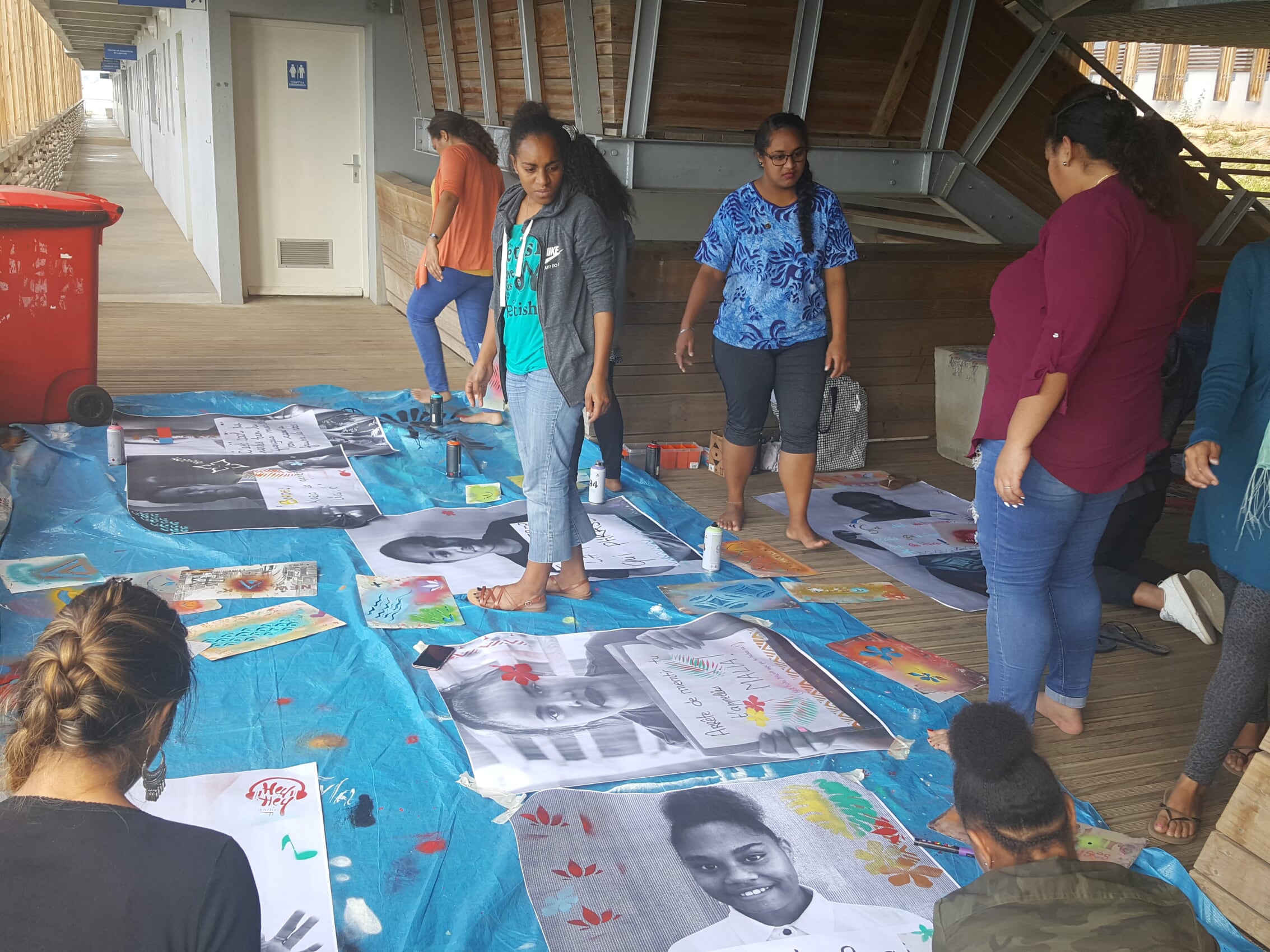

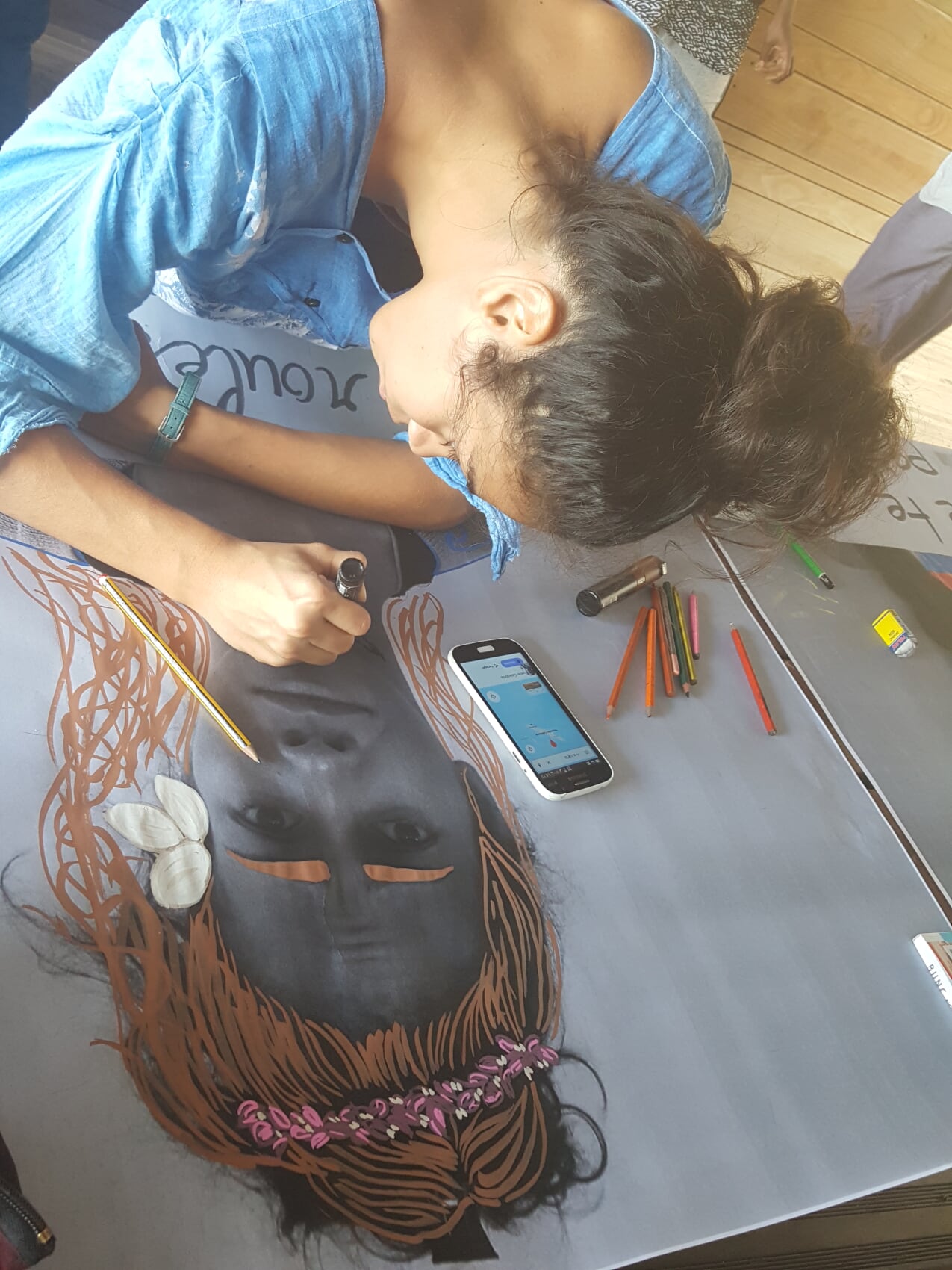

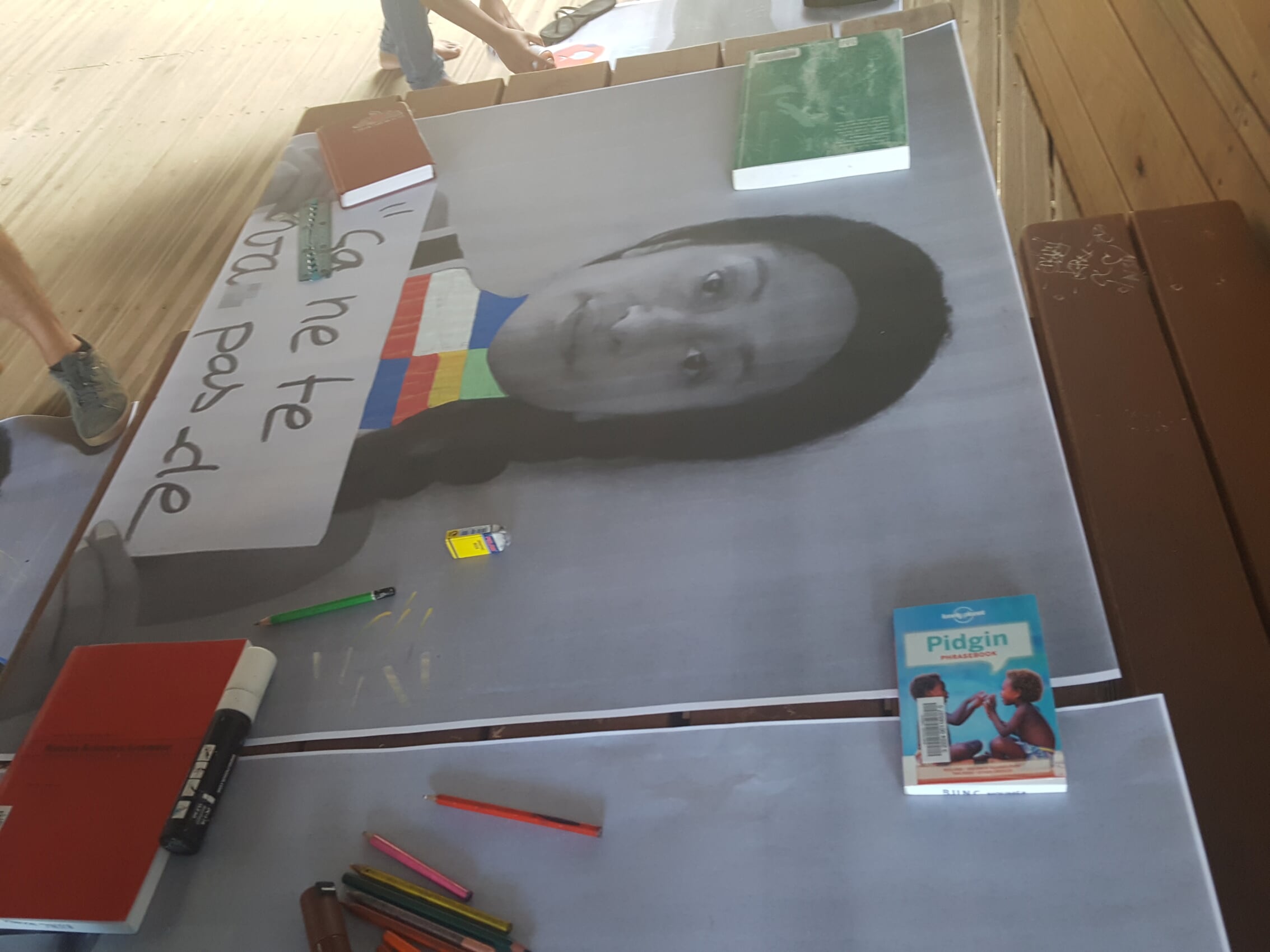

A creative collaboration took place with professional graffiti artists Paul Barri alias PaBlöw, and Yann Skyronka, alias Sham Graff. They helped students make posters by aestheticizing their self-portraits printed out in extra-large formats.

GALLERY 4: The making-of-scenes: students redesigning their self-portraits with Yann Skyronka

The public’s reactions were immediate. During the paste-up activity, some passers-by would halt while others were amused. Local media took interest by showcasing the students’ narratives. This gave them recognition, for once, they felt their stories were taken into consideration as serious matters. In turn, the presenters of a TV show shared their own experiences of linguistic micro-aggressions.

GALLERY 5: Israëla Raleb presents the project on the TV show ‘#lelien’ (Nouvelle-Calédonie la 1ère)

GALLERY 6: ‘From a class assignment on linguistic micro-aggressions to Street Art in Noumea’

Everyone has experienced normative attitudes regarding their language(s) or the way they speak but very few denounce it publicly. And this is precisely how linguistic micro-aggressions operate. They are maintained by ideologies that justify monolinguistic visions of society (one-language policies) paired with mononormative idealizations of languages (the belief that there is exclusively one ‘correct’ or ‘authentic’ way of speaking).

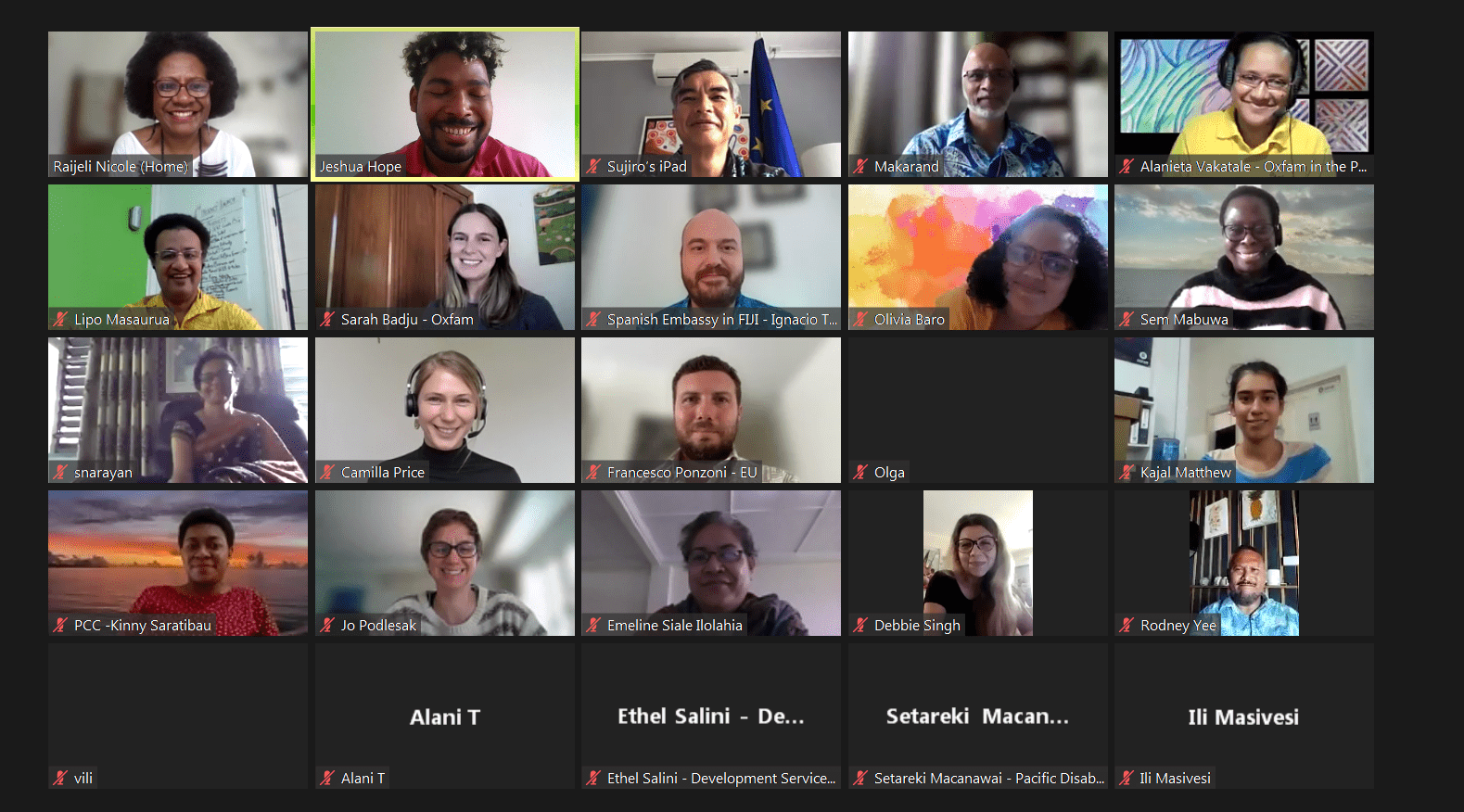

The ‘AK-100’ project has also been presented through several conferences in New Caledonia, Fiji, Vanuatu, France, and England. It is interesting to note how, wherever the location, people easily relate to the students’ visual narratives of linguistic micro-aggressions. It is a daily behaviour we can now look upon differently.

Further academic reading on language-based discrimination:

Blanchet, Ph., 2016, Discriminations : combattre la glottophobie, Paris, Textuel, p. 192